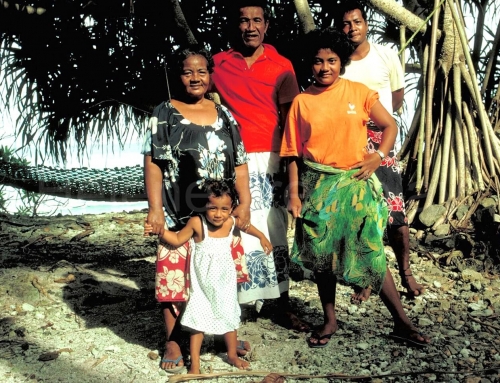

The Fihu Family

Selwyn Fihu, aged 47

Agnes Fihu, 40

Michael, 20

Jennifer, 17 (absent)

Nash, 13

Christopher, 7

Max,3

5 pigs

15 chickens

Nareabu,

January 29

The boat is coming!

6:00 The church keeper beats on an empty gas canister hanging from a breadfruit tree. The Fihu family rise quickly, put on their church clothes and quietly join the other members of the community crossing the open field in the centre of Nareabu Village. In the church, Nareabu’s only cement building, one of the women lets out a high, piercing cry, the first note of the morning psalm.

6:30 On his return, Selwyn looks for privacy on the stretch of beach that slopes down from his yard. The beach and the bush are the village’s only toilet facilities. Minutes later, a man runs by, shouting “The boat is coming!, The boat is coming!” The white silhouette of Compass Rose 11 is passing the coral reef on its way to the main town of Buala. The ferry has been out of service and everybody has been waiting for its return.

Michael, Selwyn’s oldest son, does not have a minute to lose. He is now two weeks late for the beginning of the school year at college in Honiara, the nation’s capital. His sister, Jennifer, managed to get to her school in Honiara before the boat broke down. With his jeans, T-shirt, and earring, Michael already looks like a city boy. Now he rolls his few possessions in his straw sleeping mat and scrambles down the mud slope between his home and the beach, where Selwyn is waiting in his tree-trunk canoe to row him to the reef.

Only six young men left in the village

Agnes, his mother, waves her hands to attract the attention of a motor-boat taxi racing full-speed toward Buala. The boat, already full of people, swirls around and heads in the Fihus’ direction to wait beyond the reef. Michael puts one foot in his father’s canoe, then turns. Behind him, Agnes is waiting to say good-bye. They shake hands,- shyly avoiding each other’s eyes.

Father and son paddle rapidly toward the motor boat. Her skirt trailing in the sea, Agnes stands with Christopher and Max, watching the boat disappear around the curve of the land. With today’s departures, there are only six young men left in the village.

Agnes knows her son is happy now. Just last night, he again exclaimed: “I can’t wait to leave this muddy village. There is nothing for us young people here.” He is right. The elders of the village have opposed any special programmes or activities for the young, who, they feel, should be content to help their parents work the land. Selwyn does not agree with the old people and yet he fears for the future of the young who leave for the capital. “What will happen to them if they don’t have-the land to fall back on?” he asks. Of his son, he says: “This is not the Michael we used to know. He was happy, helpful; now he is never satisfied.” But Selwyn knows he has impressed on Michael the need to be a leader if one wants to change things.

Five houses in 23 years

Selwyn fears for the future of the young who leave for the capital. “What will happen to them if they don’t have the land to fall back on?” he asks.

Because of their fragile building materials and the cyclones that frequently hit the region, the Fihus have had to build five houses in 23 years. Now they are building separate quarters for the boys; the girls will stay in the house with their parents

The first thing one notices when entering the house is the calendar with which Selwyn plans his family. He follows his wife’s menstrual cycle very closely: Selwyn cannot afford any more children.

The call for communal work

7:00 The church gong sounds again. The church and school bells regulate life on Santa Isabel. This one is the call for communal work. A wall must be built inside the school building, to form two classrooms. Some men are needed to weave sego palm leaves together, and others to layer them into a wall. The primary-school bell calls the children, who have their own communal work. They pick up dry leaves and sweep the classrooms’ cement and dirt floors.

Nash and Christopher leave the house, still chewing on their boiled sweet potato. Selwyn starts a fire under the smokehouse to dry copra (coconut meat) and pandanus leaves, which are used to braid mats. Then, bush knife in hand, he strides away, with Max at his heels, leaving Agnes to wash the dishes under the outside water tap. Dense smoke rises through the fruit trees that surround the house, and rays of sunlight filter down, accentuating the peacefulness of the moment.

He was happy with what he saw

Selwyn’s wife was chosen for him by his uncle. He admits that he was nervous before they were introduced, so he hiked through the forest’ s plantations up to her mountain to look at her through the branches of the trees. He was happy with what he saw. Agnes has always been very shy and never attended school. Even now, she avoids speaking Pidgin English. Selwyn says: “With an uneducated woman, you are sure you will always have food to eat and a mat to sleep on.” But Selwyn insists on education for his sons and his daughters and will let them choose their own marriage partners.

“Women give life, just as the earth does,”

8:00 Agnes prepares to go to one of the family’s gardens near Jeevo, her mother’s village, a half hour ride away by canoe. In truth, it is her land, as land is inherited on the woman’s side. “Women give life, just as the earth does,” says Selwyn to explain the tradition. Paddling quietly, Agnes sings to give herself rhythm. There are more and more motorboats now. “Once you discover how fast and easy it can be to get from one place to another, the will to paddle leaves you,” she says softly.

From this particular garden, she will harvest sweet potatoes. Coconut and bananas grow in another grave. There is enough land for everyone on the island. The Fihus don’t even know how much they have. But in spite of the abundance of land, it is difficult this year to find a variety of food to eat. The pineapple planting was not planned well and the harvest is over. Cassava and yams have just been planted, and this year’s papaya and cucumber crops were destroyed by seven months of drought

10:30 Nash runs home during recess to grab a piece of sugar-cane. After waiting for his sister to leave, Christopher comes in to serve himself secret! y from a cache of dry navy biscuits.

Laying an egg between the family Bible and some school books

1:00 Selwyn comes home at lunch-time to tend the small shop in the corner of his house, where he sells tobacco, tinned beef and fish and small sundries. With this income plus the income from the copra that he sells, he just about manages to pay for his children’s education. Michael will become a teacher and Selwyn will pay for Jennifer’s schooling for one more year. When she finishes Form 3, she will have to look for a job. He is ready, however, to invest in schooling for Nash. She is the brightest of his children and eager to learn.

Selwyn searches for Max, but the only living thing in the house is a hen laying an egg on the table between the family Bible and some school books. Maxis running around with cousins and friends, and finally, his father finds him and gives him a piece of fish and a sweet potato. He is tired and grumpy, so Selwyn ties the child on his back with a cloth and Max promptly falls asleep.

Her canoe disappeared while she was in the garden

2:00 Maxis still asleep, strapped to his father’s strong back as Selwyn cuts bamboo for the boys’ new house. Agnes returns, a little excited. Her canoe disappeared while she was in the garden and she had to ask for a ride back to the village. “Someone must have needed it,” says Agnes, not thinking for one minute that it could have been stolen. She asked Jeevo’s villagers to tell the borrower to bring her canoe back. She carries the sweet potatoes to the water tap and starts washing them, letting the water fall on her head and body as well. Refreshed, she climbs up the slope to her kitchen, lights the firewood and starts making bitis, a pudding of shredded sweet potatoes and coconut milk.

3:00 The morning was silent, but now children are yelling and laughing. At school, the afternoons are devoted to sports and games. As these activities are finished and the children run home, the sky turns dark gray, the wind gusts, and the tropical afternoon rain starts. Agnes sits on the floor braiding sleeping mats

Children now refuse to eat the traditional food

5:30 The church gong announces evening prayers. Agnes cannot leave her kitchen, so Selwyn will have to keep Max silent during the service.

6:30 Selwyn pumps the kerosene lamp while the family sits on the floor mat, serving themselves from a plate of fish and sweet potato. There is no rice, no canned food. “Some children now refuse to eat the traditional food, but in this house, we will keep on eating the food our garden provides for us,” says Selwyn. “It is nature that makes us truly rich.”

8:00 The bell rings for the last time to call the school children to prayers. Once again, they put on their church clothes. They thank God for the day that is ending, sing psalms and return home to bed. Christopher and Max, not wanting to miss any of the conversation, fall asleep lying on a mat beside their mother. Agnes will move them into the room she shares with Selwyn when she is ready for bed. At the moment, she is using shells to decorate a jar, which will serve as a vase at the church.

What else to do but sleep?

9:00 The village is now still. It is low tide, and on the empty beach, two teenage boys walk hand-in-hand, trying to stretch the day and shorten the night. Like Michael, they say: “In this village, when it is dark, what else is there to do but sleep?”