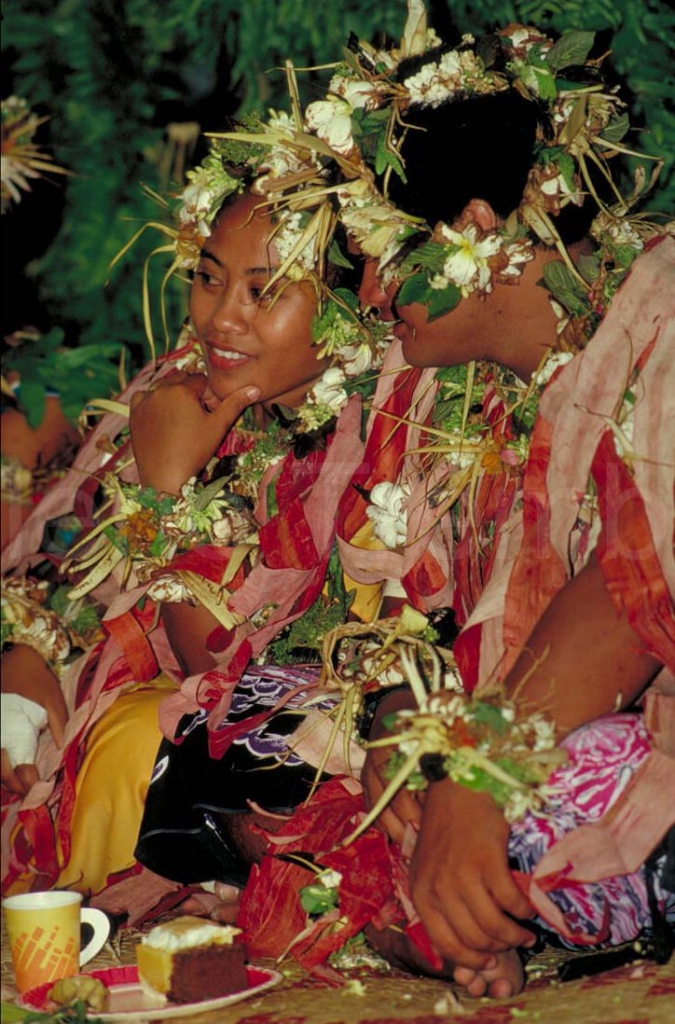

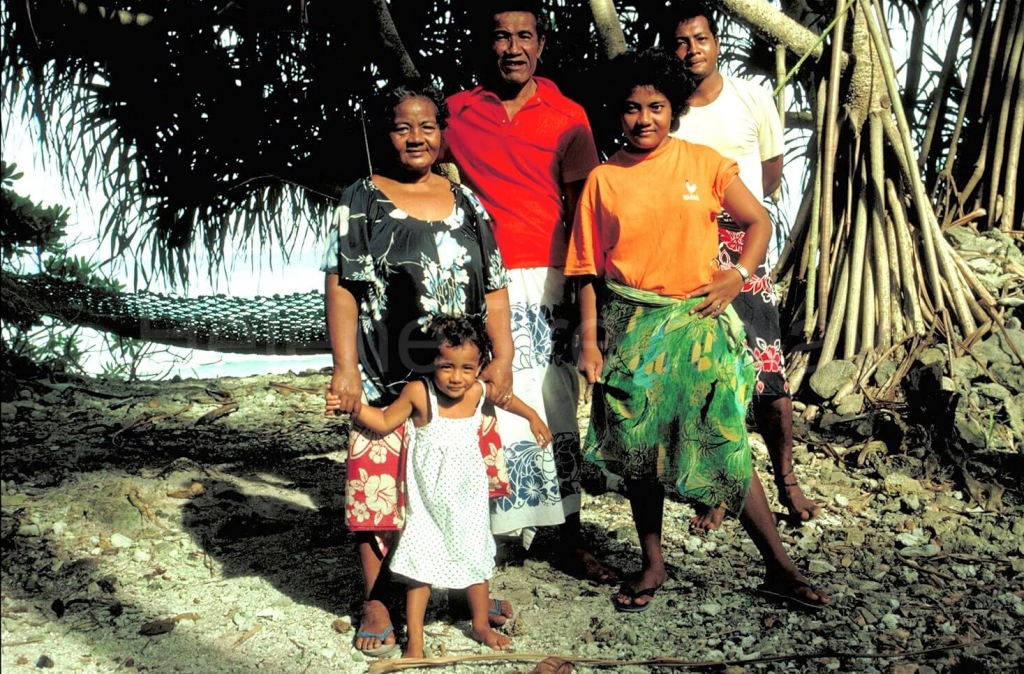

Vitoli Temou’s Family

Vitoli Temou, aged 62

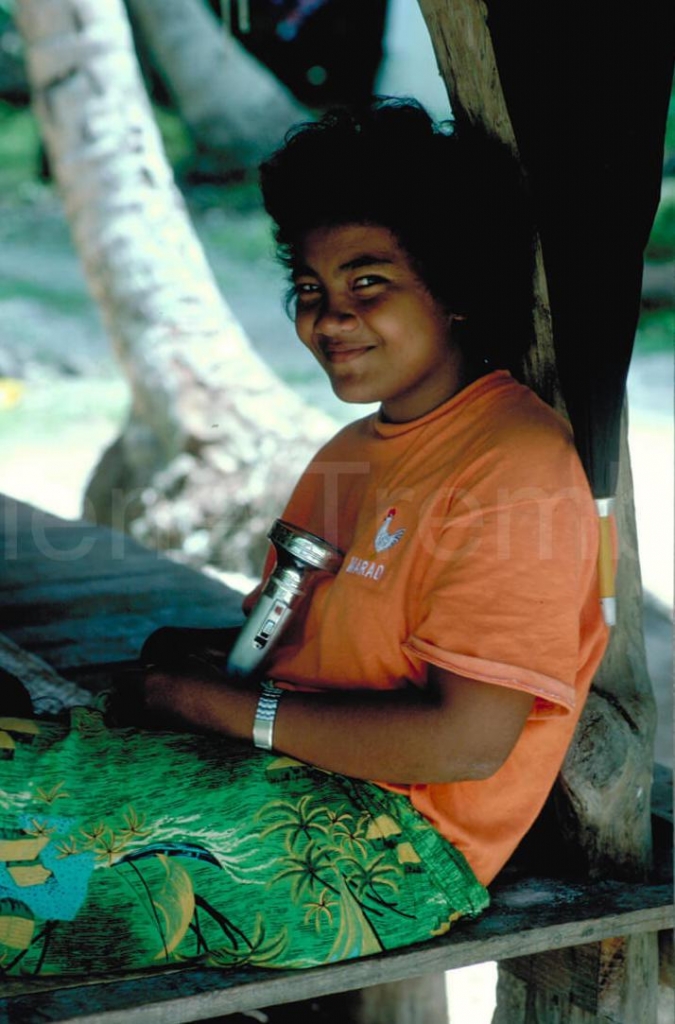

Marao Vitoli

Talamoni, 27

Nome, 25 (absent)

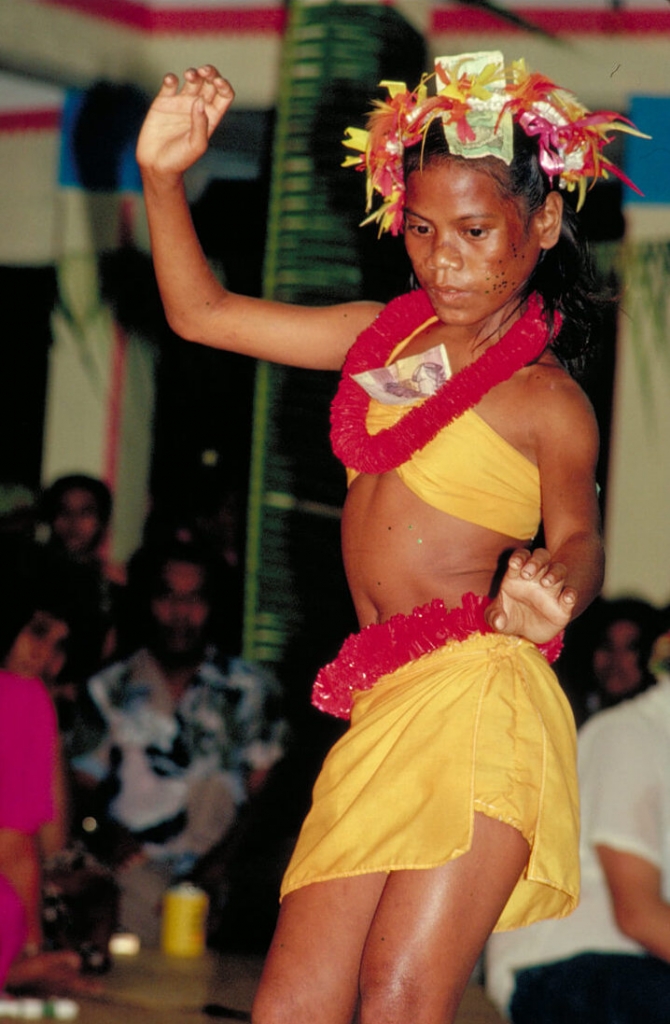

Sulufaing (Sulu) 16

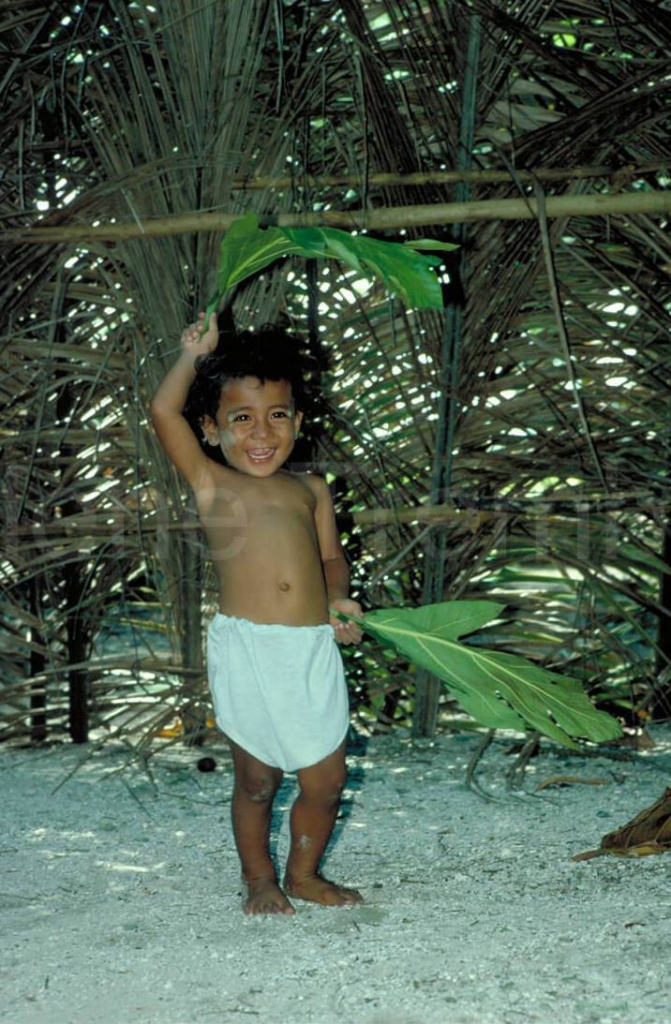

Galuola Ta1amoni,2 (5)

10 pigs

87 chickens

2 dogs

2 cats

Funafuti,

December 29

100 metres from the wild Pacific Ocean

It is still dark and the moon shines. Vitoli rolls off the side of his open house, grabs his fishing spear and slings his woven basket over his shoulder. He goes in the direction of Funafuti’ s only road, which will bring him to the narrow tip of the island, where, he says, fish are numerous. Vitoli knows many ways to fish but will amuse himself this morning with his favorite – spear fishing. He walks along the quiet road, separated from the calm blue lagoon only by a few coconut trees 100 metres from the wild Pacific Ocean. There are few houses here. Most of the 2,810 people of the country’s capital island live in crowded conditions at the other end, in Tuvalu’s only city.

There is little fresh rainwater

Land is in real demand in Tuvalu, especially on Funafuti. In 10 years, the population has increased so much that there is not enough bush material left to build traditional houses; there is little fresh rainwater (groundwater is not potable); and the soil is tainted by the salt-laden winds, limiting agricultural development. In addition, much of Funafuti’s land was excavated by the Americans to build an airstrip during World War II. The huge holes Tuvaluans call “borrow pits” have never been refilled. If they were, as everyone dreams they will be someday, there would be more space for planting.

Tea with navy biscuits

6:00 Marao, Vitoli’s shy wife lights the fire in the outside kitchen hut to prepare tea, which she will serve with navy biscuits and the fish left over from last night’s dinner. Now her daughter Sulu rises, rolls up the family’s sleeping mats, folds the sheets and puts them away with the pillows on shelves made of tree trunks. Then she takes the coconut branch broom and sweeps the yard, a daily ritual, as the constant ocean wind scatters the dry leaves of the coconut, breadfruit, banana and pandanus trees that surround the house.

This is the season of the west winds, which bring cyclones. In 1972 cyclone Bebe destroyed all houses and trees on the islands. The cement-black houses that now form the main village were built with relief funds. Vitali has one of the few traditional houses remaining on Funafuti.

6:30 Vitoli comes back with six fish and sits clown to breakfast. Marao has already finished eating and takes the fish down to the lagoon to clean them. Vitoli feeds the hens, while Sulu dresses little Galuola, her older brother Talamoni’s illegitimate child, whom the family has adopted.

Graduates have few options

Sulu is on Christmas holiday, having finished her fourth year of secondary school. Tuvalu’s only high school (250 students) is situated on the outer island of Vaitupu, so Sulu boards there most of the year. An intelligent and hardworking girl, she ranks among the first five of her class. Next year will be the last year she can study in her country. A part from training at the Maritime School (the money that seaman send back home is of great importance to family income), graduates have few options. Sulu hopes to get a grant to study overseas- in Fiji, New Zealand or Australia. Vitoli wants his daughter to study medicine. Sulu prefers mathematics. But the government might give her a grant in another field entirely.

While Vitoli pounds coconuts to feed the pigs, Marao scatters grain for the hens. Vito li has been in the egg business for the last five years. But the hens are not laying well and he is beginning to doubt the quality of his imported feed.

The people on the outer islands still live off the land and the sea, but here on the capital island, shops provide more and more imported products such as rice, canned food, flour and cooking oil. Vitali’s family’s diet has changed considerably.

Only Sulu has escaped her father’s severity

8:30 Talamoni, who has stayed with Galuola’s mother in the village, arrives with two cousins to cut the top leaves of the coconut trees to use as decorations for a relative’s wedding tomorrow. Vitoli and his son are known in the village for not being easy-going and they don’t get along.

In fact, Vitoli leads a very isolated life and is a strict and intolerant man. “In the village,” he says, “they don’t like me because I still beat my sons.” Vitoli is proud to add that, even at their age, his two sons let him beat them without protesting. He would like his sons to come and care for the hens, so he could rest like a man his age should. But his sons stay away.

Talamoni was an outstanding graduate of the police academy in Fiji but was caught stealing and lost his badge. He has since been in jail many times. Talamoni says he prefers the traditional life and fishing to being in the village, but living with his father is too difficult. His brother Nome lives in the village with his wife and rarely comes to see his father. Vitoli’ s third son committed suicide in 1981.

Only Sulu has escaped her father’s severity. “Girls marry and leave to live with their husband’s family. It is useless to beat them,” says Vitoli.

The minute I stop working, I become restless

10:00 Talamoni has gone fishing and Sulu is gathering firewood with a school friend. Vitoli sits cross legged, caressing Galuola; all his severity has melted away, and he displays only love for his grandson. By tradition, his son’s children belong to his family, so it was important for Vitoli that the child not be raised by anyone else.

11:30 Marao embroiders a pillow for Sulu to take back to boarding school, while Vitoli fills buckets with rainwater for his chickens from his 1,000-gallon storage tank. “The minute I stop working, I become restless,” says Vitoli, coming back to sit beside Marao. “But a few minutes after I start again, I want to rest.” His wife has taken out her old, rusty sewing machine and Vitoli helps her get it started. Vitoli lives up to the Tuvaluans’ reputation for being adventurous travellers. He left his home island of Nukulaelae with his father in 1936 to go to Kiribati and Phoenix Island; and again, during World War II, to go to Canton Island to work as a driver for the Americans.

Then he worked in the gold mines of Fiji and on Christmas Island for the British, who were doing nuclear testing. By then Vitoli had married Marao, the sixth woman in his life. Only the children they have had together have survived. If his other children had lived, Vitoli would have 14.

In 1961, Vitoli came backhome to care for his aging parents. He would have lost his right to the land and to the title of matai (as the oldest son) if he hadn’t returned. “Without land and today without an education, you just can’t live,” he says. As the matai, Vitoli is responsible for the distribution of the 10 plots of land scattered throughout the country to all his family members. The land has been passed down through generations of individuals and family groups, and ownership is very complicated. Land establishes a family’s status. Village gossip has it that Vitoli’s isolation is due to a family fight over land distribution. Vitoli doesn’t talk about it.

Eating raw fish crystal in the clear water of the Pacific

3:30 Lunch consisted of tea and small reef fish caught by Talamoni, and after a siesta during the noon heat,Vitoli goes back to work. He moves the hens’ pen and shovels the dried droppings to use as fertilizer for the garden where he is trying to grow Chinese cabbage and cucumbers. Sulu and her friend are in the crystal clear water of the Pacific, eating raw fish. They bite into them with relish. Talamoni slips away from the house, carrying his fishing net, his pace quickening as he approaches the ocean. As he tosses his net into the surf, he looks like a free man.

Besides two planes a week, to and from the capital, travel between Tuvalu’s nine islands is limited to one boat, the Nivaga. It makes a run of four of the islands north of the capital, stopping a few hours at each, then comes back to Funafuti for a southern run that sometimes brings it down to Fiji. If one goes to an outer island to stay, it could take months to return. When government officials visit the outer islands, the few hours the Nivaga stop is all the time they have to speak to their people.

She fears ghosts in the dark

6:30 Sulu has persuaded her friend to go with her to the village to see a film at the community hall. Her father would not have allowed her to bicycle alone, and, in any case, she would not have wanted to; she fears ghosts in the dark. The sun is setting on the lagoon and night has fallen by the time they reach the village. Their bicycles safely parked at a cousin’s house, the two girls walk to the open-walled centre. It is already crowded. Women have spread their mats and pillows and laid their babies clown to sleep. Men are rolling Gallagher’ s Famous Irish Cake tobacco in banana leaves to smoke. No one knows what they will see, but any film is welcome.

Young men stretch a large white cloth that looks like a sail between two wooden pillars, but they never do get it taut. Throughout the film, the cloth waves in the wind, adding unplanned movement to the actors in Our Lady of Fatima. The 18 Catholics on the island may know what it is all about, but the others just enjoy a distracting evening.

9:00 Once Sulu and her girlfriend leave the village, there is no more electricity. Sulu’s pocket flashlight and the half moon on the white coral sand are enough to help them avoid the holes in the road. The journey is peaceful. Even the dogs are quiet, and the ghosts have stayed away.