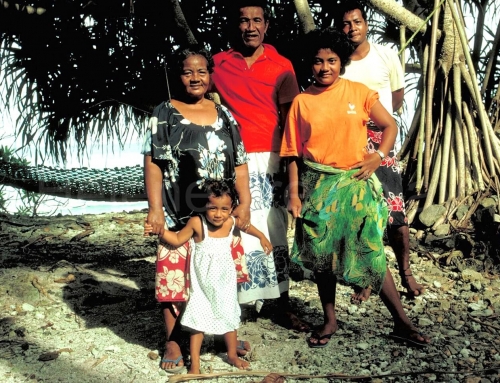

Ratu Abele Asaroma’s Family

Ratu* Abele Asaroma, aged 31

Silivia Vakaseleasi, 28

Adi Kubuyana Silivia, 11

Adi Bilivalu Maria, 9

Ratu Kalaveti Bebenisala, 7

Ratu Vilisi Ronaivana (Oscar), 5

Adi Salote Nayala, 2

1 cow

5 chickens

*Ratu (for men) and Adi (for women) are titles given to the descendants of a chieftan family.

Naseuvu Village

November 23

Concerned about the loss of tradition

5:00 At the cock’s second crow Silivia crawls from under the mosquito net, leaving her two youngest daughters beneath it; then tiptoes around her husband and three other children sleeping on the floor mat of the vale-lebo (sleeping house). She pulls out the tab of wood that serves as a lock and goes to make breakfast in her vale-kuro (cooking house) before her children leave for school. All seems fixed in time. The heavy clouds ding to the mountains of the province of Naitasiri and their mist settles to the bottom of the valley, giving the impression that the village of Naseuvu nestled there will stay forever caught between day and night. Only the rushing waters of the Waidina River, and the smoke from the kitchens’ wood fires reveal the activity in the village.

A sub-clan chief

When Silivia steps outside, her foot sinks into the muddy earth. It is the rainy season. Just yesterday, her husband, Ratu Abele, was binding the last leaves on the cooking house’ s roof, one of the few buildings still made in the traditional style. His father, Ratu Valetino, is so concerned about the loss of tradition that he insists the whole family must learn the craft. In Fijian society, power descends from the paramount chiefs to village chiefs, who distribute the garden space to their villagers, and down to sub-clan chiefs like Ratu Valetino, who represent the needs of their particular tribe. At the sound of the church’s lali (a hollow wooden gong), the three older children, dressed for the day after their shower the night before, jump up silently, fold the cotton cloths that have served as bed sheets, pile them in cardboard boxes at one end of the house, where all the family’s belongings are kept, then walk across the village. Their first words will be those of the morning’s prayers in the small wooden church.

Milk for the extended family

6:15 Adi Salote Nayala, the youngest, her legs still shaky from sleep, is the last to peek out of the door, where she discovers her grandmother squatting under an umbrella, washing the dishes at the outside tap that serves the three houses of her husband and her two sons. The child totters toward her father, Ratu Abele, who is going down to the river to milk his father’s cow. The milk will serve all 16 members of the extended family.

Nicknamed “Oscar”, after the cyclone

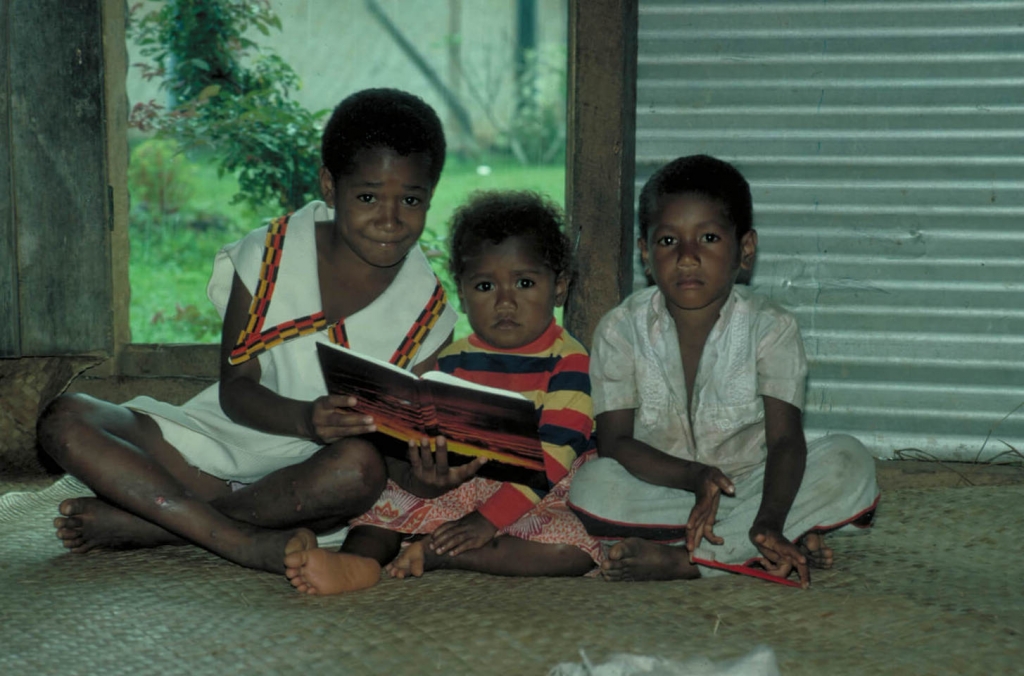

7:00 Oldest daughter Adi Kubuyana spreads a long rectangular cloth on the floor of the sleeping house and takes plates from the house’s only shelf, singing as she works. She is a happy girl with a magnetic personality. Ratu Vilisi, her brother, who watches her, is just the opposite, often whining and looking for trouble. His nickname is “Oscar”, after the cyclone during which he was born, and his family believes that that terrible night influenced his personality.

It is taboo to eat any food from their father’s plate

As Silivia and her oldest daughter bring the dalo (a starchy root), the family crawl to their positions around the cloth. No one walks when the father is in the house. Every aspect of their life, including the meal, is guided by tradition. Ratu Abele sits at the upper end of the cloth. He will be served the first and best portions. His two sons are on his left and right, the rest seated by age, with Silivia nearest the door to her kitchen. The meal won’t start before grace is said. Children must sit cross-legged, not moving until their plate is finished. It is taboo for them to eat any food from their father’s plate, and if they get up to get something, they must clap their hands twice as they sit again, to excuse themselves for having been higher than their father.

Communal workday

The family eats quietly, their silence broken only by the cali of a villager blowing the davui (conch shell). Today, Monday, is the communal workday. It is this work that has made Naseuvu so beautiful. Women have planted flowers on the village’s greens. Men have built sidewalks, a communal house and the church. Today only the men are called; the dam the villagers have built in the mountain stream is clogged by branches and rocks and the water taps have stopped running. By working together, the men will re-establish the water flow in just a few minutes.

Praying, eating and sleeping on Sunday

Ratu Abele has decided not to join the men, as he is anxious to finish the kitchen’s hearth. He could not finish yesterday, since the government, highly influenced by Protestant religious beliefs, prohibits anything but praying, eating and sleeping on Sunday. A lali rings again, this time from the school on the mountain overlooking the two villages it serves. Children are called early to remove the fallen dry leaves from the school grounds, take care of the flowers and clean the latrines.

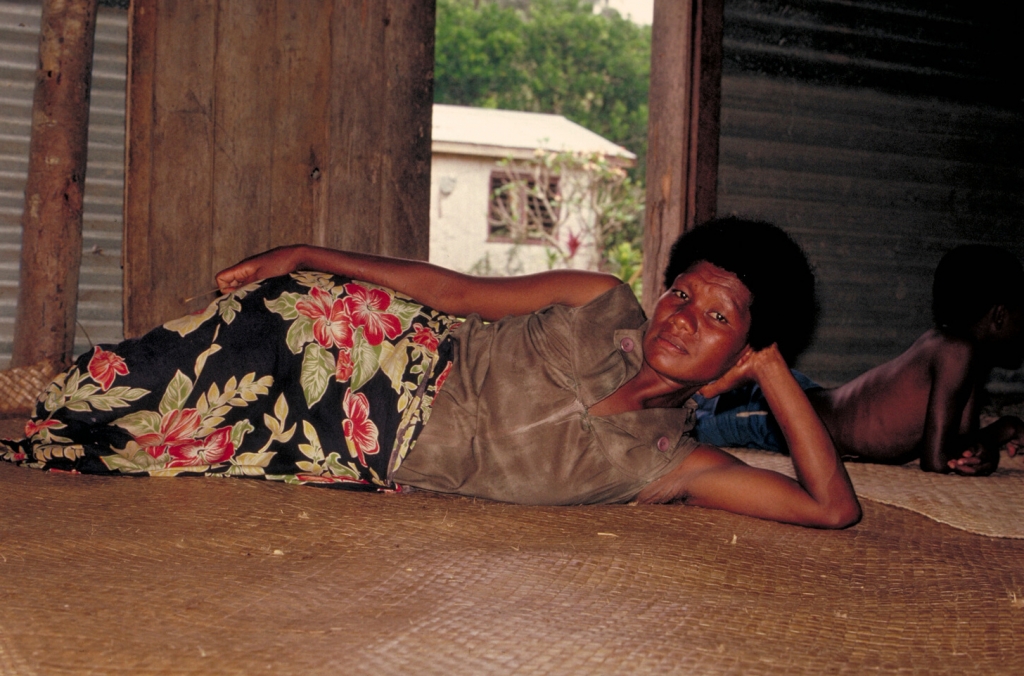

Her duty: never to let the children and houses out of her sight

9:00 The lali rings once more to tell the school cook and all the villagers the time of day. Silivia lies down all alone in the middle of her house; her pregnancy makes her very sleepy. Her two youngest children are with their father’s mother, whose duty it is never to let the children and houses out of her sight. After her nap, Silivia takes a 20 minute walk to the next village to visit her mother. The dirt road is deserted. A bus travels the road twice a day to bring the villagers to and from the capital’s market, and occasionally they see a truck coming to get the farmers’ banana crops.

Six months pregnant and tired of so many pregnancies, Silvia does not interfere with her husband’s desire for more heirs. It is her duty to serve and obey the wishes of her husband’s family.

12:00 Silivia is back from her mother’s just as the school gong·announces lunch for the children. Silivia, her husband and the two youngest will share the meal cooked by her mother-in-law.

Subsistence living is giving way to a need for cash

1:30 Machete and fishing pole in hand, Ratu Abele and Silivia walk single-file along the rocky river bank to fetch vegetables from their garden. Oscar gets to come along, but an upset Adi Salote stays home. From the tone of her cries, she must believe they’ll never return. Ratu Abele, Silivia, and Oscar cross the snaking river twice to get to their garden. All of Ratu Abele’ s land is near the river. He has planted dalo, cassava, banana, breadfruit and yams. Half of the harvest will feed his family and the other half he sells at the market once a month. But subsistence living is giving way to a need for cash; now the family needs money for schools, clothing and the imported canned foods, rice and spices that they have become accustomed to. The couple do not know, and do not worry about, the size of their plot. They know they could clear as much land as they would need to earn more cash. But the problem is that there is no more land close enough to rivers and roads to get produce out to market.

Heading back home with seven fish for dinner,

3:00 Silivia and Ratu Abele’s clothes, already damp from crossing the river, are now wet with sweat. After planting new cassava plants, the couple select the best dalo leaves, dig up a few yams and pick bananas. Ratu Abele piles them onto a bamboo raft, which he pulls upriver to the village, with Oscar perched in the middle. Silivia stays behind to fish for tonight’s dinner. At the bend of the river, where fishing is plentiful, a dozen villagers already stand in aline along the bank. A daily necessity, fishing is also a time for relaxing. Silivia laughs and jokes and visits with friends, heading back home with seven fish for dinner, long after the lali has announced the end of school

Ratu Abele reaches for the guitar

6:00 The sun appears from behind the clouds just before setting, illuminating the greens of the mountain side. The church’s lali sounds. As her children leave for evening prayers, Silivia goes to her kitchen.

6:30 Back from church, Adi Kubuyana goes to the tap to wash the morning’s dishes and then waits, ready to help her mother. While the dalo leaves boil, Silivia peels the cassava. In his father’s house, Ratu Abele mixes the kava. First he crushes the plant’ s roots into a fine powder, then wraps it in a thin-spun cloth. He will soak the kava in water in a big wooden bowl used for the nightly “kava ceremony” attended by the men. His father, the chief, sits near the central door in the upper end of the house, where the others lower in rank are not allowed to sit. Ratu Abele’s older brother, the chief-to-be, will serve the kava in a half coconut shell. Ratu Abele reaches for the guitar.

Not enough food would be a shame

8:00 Silivia eats alone with her children. There is more than enough food. Not to have enough would bring shame on the house of Ratu Abele. After the meal, two school girls arrive, to rehearse for the annual year-end show. Adi Bilivalu and her girlfriends practice the traditional songs and the motions of the hands that accompany every word, lulling little Ratu Kalaveti and Ratu Visili to sleep. Adi Salote dozes, her head resting on her mother’ s knees.

9:30 The house is quiet now. On the shelf in a jar used as an oil lamp, a flame is burning and will stay lit all night. Traditionally, it was to keep the bad spirits away, but Ratu Abele’s family has forgotten this and the lamp is now “just the way it has always been”. It also makes it easier for anyone to go to the “little house” in the yard during the night.

Asleep on the doorstep

11:00 Silivia lies asleep on the doorstep, waiting for her husband’s return to serve him dinner. That will be whenever the men have emptied the kava bowl and finished their songs. Ali the village kitchens are as new as Silvia’ s. The fragile buildings must be rebuilt after each cyclone. Ratu Abele has rebuilt both his houses three times. Ratu Abele decided to rebuild the roof and walls of his sleeping house with the iron, and use bamboo and leaves for the kitchen. Adi Salote won’t be the youngest for long; her young mother is six months pregnant. Although tired of so many pregnancies, Silvia does not interfere with her husband’s desire for more heirs. It is her duty to serve and obey the wishes of her husbands’ s family.