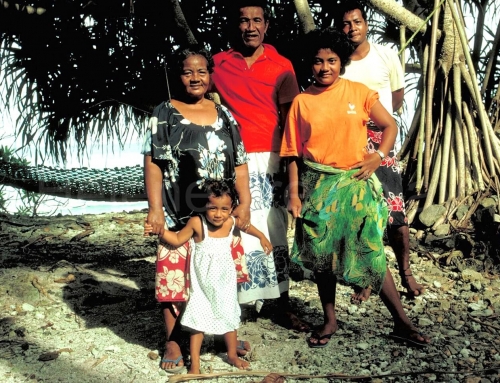

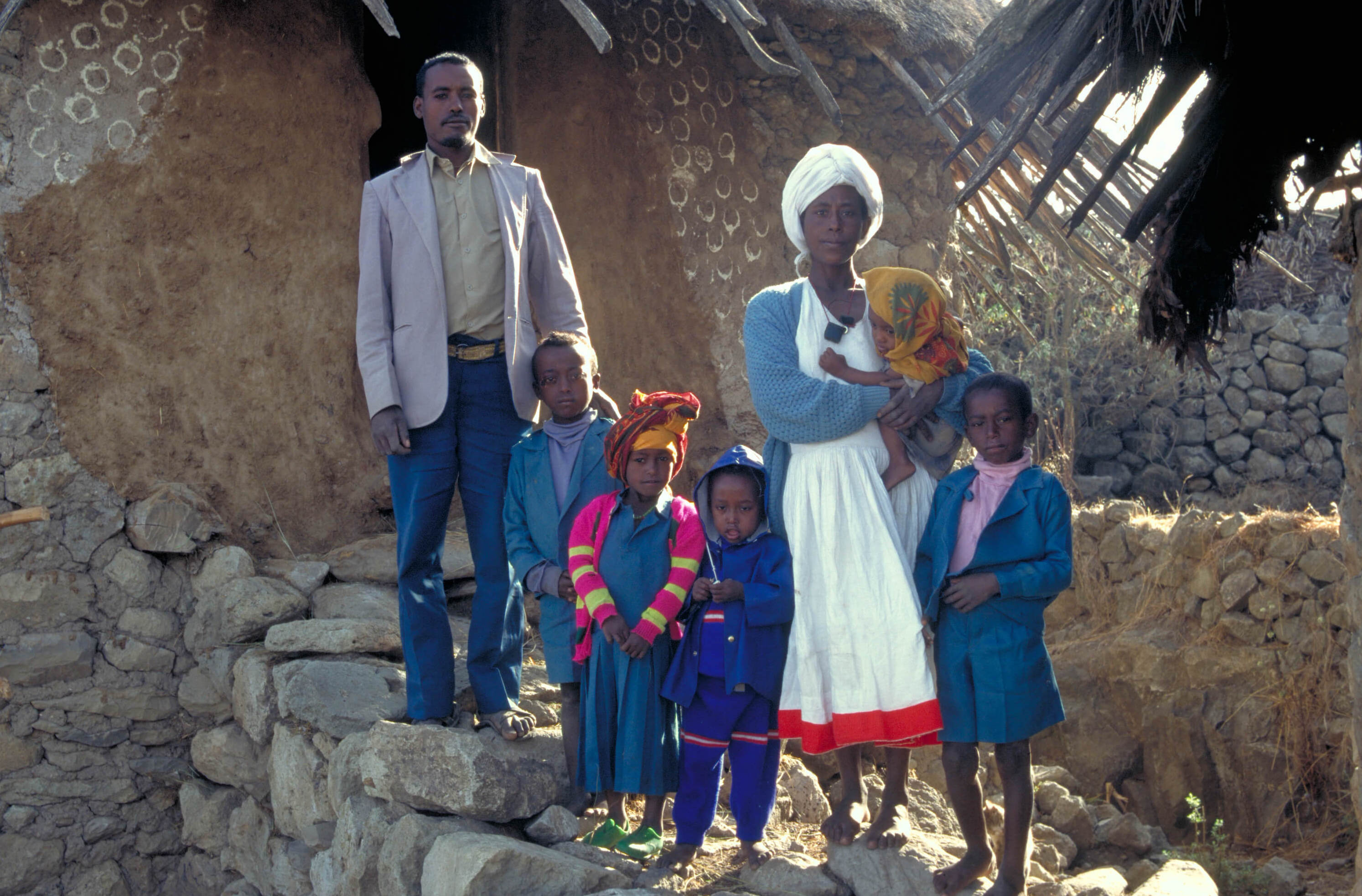

Belay’s Family

Belay Seyfe, 35

Bizunesh Gebre Medne, 28

Demelash Belay, 10

Teshome Belay, 8

Wenynishet, 6

Mulat, 4

Zewdnesh, 18-months

Animals:

2 oxen 1 small ox [note]

1 cow

1 calf

1 horse

1 donkey

15 sheep

1 rooster

5 hens and chicks

1 dog

1 cat

Village of Tosign Amba

May 21 (May 12, on the Ethiopian Calendar)

Jumping out the sack of hay

5.30 a.m. The first birds sing shortly after the rooster and in the “maedbet” (food house) Bizunesh begins to pray. She thanks God for having seen her safely through the night and asks him to accompany her through the day. If he does, he will have to be fast because it is with energy that Bizunesh goes trough her days. She jumps out the sack of hay she has been sleeping on with her two youngsters, Mulat and Zewdnesh.

Preparing for the coptic orthodoxe feast

On the second floor of the “sarbet” (sleeping house), her husband Belay is up with the same bird’s song and immediately ready to go. On the floor beside the door, the blanket under which his three eldest are gathered forms one big ball, the children sleep so tightly together. He packs grilled corn kernels onto the donkey and leaves for the hour-long walk to Seladingay’s mill to have them ground. His wife wants to brew tella for the Mariam’s (Mary, the Mother of Christ) feast coming up on May 21. The local beer will be in great demand for the Coptic Orthodox feast and the income generated at the Saturday markets is crucial to the family’s survival.

Women’s time to go to the latrines

Bizunesh goes out to one of the family fields away from the stone-fenced compound. Before sunrise and after sunset is when women can use the fields as latrines. On her way back to the dry-season kitchen she picks up the donkey and sheep dung which Teshome, her cattle-keeper-son, has brought back from the grazing area yesterday. It burns slower then cow-dung. It takes less fuel and lasts longer. She starts the fire to cook the next three days’s supply of injera, the traditional sour pancake-type bread eaten at every meal.

The loving leader of the house

6 a.m. Bizunesh runs up to wake the three older children. They are needed to assure the family’s daily survival. With one foot, she gently shakes her eldest Demelash, always the one sleeping nearest to the door. “Come on, come on, time to get up,” she says firmly enough to announce that no one fools around with her decisions and that she is the loving leader of this house. One by one, the little heads come out from under their cotton blanket (5) and without a sound, wrapped in their shammas, the youngsters get up. They know what they have to do.

But, first they come into the kitchen to sit near the fire and the cat purring there. The children sit on the round bench (6) that surrounds the hearth. Not for long, as sitting watching mama cook is for the very little ones only and four-year-old Mulat knows this brief privilege coming to an end. In a few months when Teshome starts school, he will be the family’s full-time cattle-boy.

Source of the household laughter

Wenynishet can wake up slowly, her responsibility is her baby sister. Zewdnesh has demanded her mother’s breast several times during the night, but she is now sleeping quietly. No one wants to wake this one up despite the fact that they all love her. She has begun repeating what everyone says and most of the household’s laughter comes from her sayings.

Assisting plowing before school

Demelash is off to one of the mountain neighbours to ask him to bring the oxen’s neck harness and “maracha” (plowshare) that his father will need upon his return. There is a day of plowing ahead and Demelash is assisting until school-time.

Teshome, the cattle boy, fetches grass to feed his animals. He sits on the half-inner wall separating the animals from the small family space, assuring himself that all have eaten well. Grazing the bare mountains of North Shoa is not enough.

The minute her injera are done, Bizunesh serves some to her children with “dilih” (7) the spicy red sauce, to dip their bread in. She has no time to prepare a special “wat” (sauce) in the morning. She grabs her earth jar, puts it on her back, and with her typical quick, dynamic steps, heads for the nearby spring to fetch water. She then starts a fire in the main kitchen to boil water for the morning coffee. It will be ready when her husband comes home.

Roasting the white coffee beans

Part of the energy Bizunesh puts into her work is to assure the means to have her coffee morning and night. Coffee at midday happens rarely because of lack of time. Having coffee in Ethiopia is a meaningful moment, done as a ceremony, and it takes time. Bizunesh likes this special tradition and she and her husband accept the lengthy preparation as a moment to relax. Bizunesh lights incense in the house while she roasts the white coffee beans. When ready, she lifts the plate to her nose, lets her children smell it and the round kitchen hut fills with wonderful odors that raises the pleasure when the coffee is finally served.

Well planned! As Belay comes in putting down the bags of ground maize, his wife naturally serves him the first of the three cups of coffee. The Belays have no watch and seem to have little to do with either Ethiopian time or Western time. They have found their own way to manage and survive where many do not.

He would watch her over the fence

It was Belay who first spotted Bizunesh. He had gone to her village where he had an uncle. He was hiding there to avoid the military draft where he would have been taken off to war. Bizunesh passed by every day and he would watch her over the fence. “I saw her and I knew she was the one I wanted,” says Belay. One day, as she was going to Seladinguay, he asked her if she could buy soap for him. He did not need soap, it was an excuse to get close to her. It worked, and she fell for him too. Before marrying they both agreed on what they wanted in life.

Bizunesh not only wants her coffee but also that her children be educated. To have this, and enough to eat all year, is a big dream in the Ethiopian mountains. It requires that she and Belay work together as a team. And they have done so from the beginning.

Little Zewdnesh’s cry to “mama” is a reminder of their plans to have four children only. Now with five, they think they have not properly understood the information about family planning. “Breast feeding does not work as a contraceptive,” says Belay and Bizunesh doesn’t trust other means. She says there is so much gossip about how the pill is bad and she is afraid to take any. (14)

One more animal also means more dung

7.30 Wenynishet brings the baby on her mother’s knees. Bizunesh kisses her tenderly, gives the baby her breast and covers her with her shawl to keep her warm. She resumes her coffee serving.

Teshome lets the sheep out and then the cattle, leaving the oxen to his father for plowing. The mare follows slowly. Belay has tied her right back leg to his neck. If he lets her go free the mare will go back to its old home. The mare is Belay’s last purchase two weeks back. He was able to do it with the help of his father who loaned him the 300 Bir [US$40]. “My father said to me ‘son, you buy yourself a female horse, the dung will serve has manure and soon you will have a small horse that you can sell and then another one will come. With the money you will receive from the young ones you can pay me back’.” Although his father added “son, do not worry about the time this will take you,” Belay worries. “I just can’t live when I am in debt and this is a big one I have now with my father.”

But one more animals means more dung and it is of utmost importance for survival.

Dung is used as fuel, fertilizer and in building furniture or household articles.

Four-years old is the agreed age to start working

His duma (walking stick) in hand and shemma on his shoulder to protect himself from the burning sun and unpredictable winds, Teshome walks down the mountain towards the water springs followed by his shy four-year-old neighbour who brings his own family cattle to graze.

Teshome has been training his younger brother, Mulat, for a year now. Four years old is the age to begin working, but Mulat still has a few months of choice ahead and decides today to stay with his mother who complies with his request.

The lonely years of cattle boys

Belay harnesses the oxen after seeing his son away. Apart from the few men born in the cities, everyone in Ethiopia has memories of their years has cattle boys. For Belay they were lonely years. “My parents were scared I would meet bad boys and did not allow me to keep the cattle in the group.”

Belay, not wishing this loneliness for his sons, allows them to spend the days with their friends. He trusts them but has set rules about the games they are allowed to play while the cattle graze lazily near the spring rivers. No betting is the rule. “They first begin betting with rocks, then they play with buttons and the first thing you know, they are playing for money and this I do not ever let my sons to do.”

It is dangerous to step over the line

But the days are long without balls or toys so Teshome sometimes, when he’s sure no one is looking, lets himself play a game. Rocks are plentiful for the cattle-boys.

Rocks abound where his father is too. In the field, behind his oxen, he not only turns the dry earth but also the heavy rocks. They give shadow to the fields and keeps moisture in the soil but Belay says if he leaves them there in the field it’s only because there is no place to put them. If he puts them on the side they will automatically be on someone else’s land and this could get him killed.

Too many people for too little land means that there is no unused productive land in Ethiopia’s highlands. The stress of survival on so little land gets people nervous and aggressive towards anybody stepping over the line.

At nearly 3,000 m altitude, Belay has a panoramic view of the other hills where farmers are heard calling to their oxen ahead. So much land he can see, but so little is for him.

But the feudal system and the emperors came to an end

When Belay got married he went to live with Bizunesh at her mother’s.

Only 90-minutes walk away, he was the closest one to his grandfather who lived alone. So, one day the old man asked his grandson if he would come to care for him until his death. In exhange, he would give him his land and house.

His grandfather had once owned a lot of land and many farmworkers during Emperor Haille Selassie’s time. But if he was a big or a small land-owner, Belay does not know. “He had land down in the lowlands, in the highlands, in all the different growing land the mountains offers.”

But the feudal system and the emperors came to an end with the Derg (marxist) regime. As did land-owning. The “land to the people,” said the government who became the owner of all Ethiopia’s land. Belay’s grandfather was left with five hectares of his less productive land.

Land is constantly deteriorating

Belay accepted his grandfather’s request to give half the land to one of the faithful workers living in the courtyard for over 20 years. Today, the two families do not live comfortably side-by-side and Belay would prefer to have all the yard to himself.

He would also prefer to have 10 hectares to live the life he and his wife have planned, but land is still not for sale and last year the country’s political life again changed the course of Belay’s life. With still too many farmers without land, another land redistribution took place taking another half-hectare of Belay’s land.

He says that the farmer to whom the land was given really needed it, but the decision was not easy to accept and feeding his family is becoming harder and harder. So, with what is left of his land dispersed in the very steep mountains, Belay harvested eight bags of wheat and three bags of barley on the wide land he has near the house and three bags of beans, and one of lentils lower down the mountains where his land is only meters wide.

“My grandfather use to get 30 bags with one hectare,” he says. These days are over, land is constantly deteriorating. Soils in the highlands are poor and the too large and concentrated population constantly using the soil, without crop rotation, has degraded nearly all the highlands of the country. Some land is simply dead.

We give our land away

Continuous deforestation causes land erosion in which soil slides down the steep mountains into the rivers which then carry the land into neighbouring Sudan and Egypt. Ethiopians say “we give our land away.”

But the land Belay is plowing this morning was not given to him. It belongs to one of the mountain farmers. With less then a hectare, it was not enough to feed his family, so the man went to find work as a labourer in the city, (Addis Ababa?) Belay agreed to a shared deal. He works the farmer’s land in exchange for half the harvest.

Belay has made the same deal with his mother-in-law. He has to go nearly two hours to Debre Mtsimak village with his oxen to work this piece of land that could help make the difference between survival and sliding into famine.

Pockets of famine

Despite the country’s continuous famines, Belay has always managed and has never received food assistance or help. Bizunesh says it’s because both of them never stop working. The heavens have also helped. The agro-climatic differences in the mountains of the country bring enormous differences in very short distances and at different altitudes.

There is too much rain for some, not enough for others creating “pockets of famine”.

Just yesterday in town those who have radio access heard that people are experiencing famine nearby in North Shoa and in Welo, the neighbouring state which is always the country’s most affected region. Belay has not heard this, but he knows it will be another bad year.

The short rains

The belg, the short rains that fall in February, have not come. “We have not seen rain since last August,” says Belay. This morning, the rains would have made it so much easier for Belay to turn the dry earth. He now has to yell at his bull, holding hard to the plowshare even then, some of last year’s roots do not want to come out. Behind him Demelash digs the ground with a hoe for the tough old roots his father has missed.

The ideal belg season, he explains, is when there is rain during the month of March, no rain in April and occasional rains in May. This allows a small crop that assures food until the big harvest of November. But Belay does not remember such good harvests since the year after the “great famine” of 1984.

Short rains are also necessary to fill in the seasonal river and assure water and grazing for the animals. Animals are Belay’s money in the bank. Wealth is defined by the number and type of animals one owns. It can be seen by the size of the cow dung pack outside the compound walls.

The length of the shadow from roof told her its time for school

Bizunesh is starting to brew the local drink and this will keep her in her kitchen all day. Except for the market where she goes each Saturday with Belay, she hardly goes out. “We have our coffee at home,” she says which as contrary to the culture’s tradition to have coffee with neighbours. She does not often go to church either, her morning and night prayers are enough. She works for her goals and to make it through until next harvest.

This means the family must earn money to buy grains which are at their cheapest this time of year. The family production is too small to have food all year and only when the big rains begin, and all their time is needed in the fields, will they start eating what is stored in the baskets on the ground floor of the sleeping house.

To find money, Belay becomes a middle-man, buying grains from farmers in other villages and selling them at the market. This, with the profits from the beer, allows them to buy the grains they need to eat for one week. And week-after-week they hope to have enough to make it through.

10.30 No radio, no electricity, so the morning mountain echo is still the best system of communication for the highlanders. This is how deaths and important news are announced and this is the way Bizunesh announces its time for Demelash to begin walking to school. The length of the shadow of the kitchen roof on the ground told her so. The voices of children on the mountains paths confirm it. She hands her son his school bag and off he goes.

Only 13 girls will attend grade eight

There are only four classes for the 300 children of grade one. Demelesh squeezes into the middle of two boys in the third row. Around him more than 60 children crowd the small school benches. Their ages vary from six to 16. The math lesson begins. “I like to learn,” Demelesh says.

The school director is cynical and sarcastic. He has heard too many children say they want to learn and too many parents say they want to educate their children. From the 161 boys and 140 girls that begin grade one only 30 boys and 13 girls will attend grade eight. So he does not believe Demelesh will finish his education. The biggest drop out rate is after grade one and grade two. “The peasants say they want to educate their children but they do not follow up on their word or desire,” he says. The parents drop out, too, keeping their children home to work. Easy divorce, single-women households, early deaths of parents from disease and war means children are needed in the fields or as cattle-keepers.

My parents did not understand the importance of education

The long distances and the fact that so many get abducted and raped on their way to school means that the girls are the first to be kept home. It’s only because her village was a short, 15-minute walk from school that Bizunesh has had the privilege, by the time she was 18, to be given five years of schooling. Then her father died and education was over. She had also met Belay and school benches held no more attraction for her anyway. But she says that it is because she was in school that she got married so late and not at 13 as are many girls.

Belay was not so lucky. “My parents did not understand the importance of education, they only believed in the church education.” He has never seen the school benches but he agrees with Bizunesh on the efforts that must be made for his own children. There will not be enough land for them and he dreams of seeing them get out of the mountains. And when he admits to his biggest dreams, Belay says he would like one day for his children to go to America. He thinks this dream is possible. If his mother chose to stay in the mountains some of his grandfather’s other children have made their way to the Addis Ababa and some even out of the country.

Fasting 165 days each year

2.00 Teshome and Belay have come to have injera and go back to work.

This is a period of no fasting and Bizunesh has included one fried egg with the wat. This is not allowed every day. Their Ethiopian Orthodox religion requires that they fast 165 days each year. (*)

Wenynishet walks around with her sister on her back. The minute her fire does not need attention, Bizunesh spins a small cotton ball. When she will have enough thread she can have it woven. From this cotton all the clothing, the shawls and blankets are made. They are essential in the mountains where the winds vary and turn cold suddenly. No one goes anywhere without a shawl.

5.00 School children and cattle-boys are now bringing life to the empy mountain paths. The sun is no longer burning the cheeks and Belay has nearly completed plowing the field next to the house. His energy and the strength required of him have not diminished. Nearby, Wenynishet has come to get dung from the stack for her mother to cook the evening wat.

Demelesh walks into the house, puts his school bag on a nail in the wall and walks back out with a jar to fetch water. Bizunesh is proud of her son. “My son is courageous,” she says adding “I know he is intelligent and learns well.” The admiration is mutual and Demelesh says “I always help my mother.”

No one goes anywhere without a shawl

This is a period of no fasting and Bizunesh has included one fried egg with the wat. This is not allowed every day. Their Ethiopian Orthodox religion requires that they fast 165 days each year. (*)

Wenynishet walks around with her sister on her back. The minute her fire does not need attention, Bizunesh spins a small cotton ball. When she will have enough thread she can have it woven. From this cotton all the clothing, the shawls and blankets are made. They are essential in the mountains where the winds vary and turn cold suddenly. No one goes anywhere without a shawl.

5.00 School children and cattle-boys are now bringing life to the empy mountain paths. The sun is no longer burning the cheeks and Belay has nearly completed plowing the field next to the house. His energy and the strength required of him have not diminished. Nearby, Wenynishet has come to get dung from the stack for her mother to cook the evening wat.

Demelesh walks into the house, puts his school bag on a nail in the wall and walks back out with a jar to fetch water. Bizunesh is proud of her son. “My son is courageous,” she says adding “I know he is intelligent and learns well.” The admiration is mutual and Demelesh says “I always help my mother.”

Watching the sky to see the first star

6.00 The oxen are back in the yard and Demelesh is feeding them while Belay makes a few trips with dung to throw over his fields. Bizunesh puts down the jar of water she just got from the spring and goes near the house to take a few branches of the eucalyptus trees for the evening fire. Now that the day’s work is over, the children can finally be near their mother and the smells of the evening lentil wat. Soon to come is the satisfaction to lay on the cow skin over the hay pack that forms their bed.

6.30 Teshome sits at the compound door, watching the sky. The moon is there but the sky is still too bright for him to see the first star. Until he sees it, Teshome cannot bring in the sheep — tradition says so. It’s a question of minutes now before he can join his family near the fire for a short and quiet evening. The sheep know it, they have all gathered in front of him impatient to get their cue that the day is over.