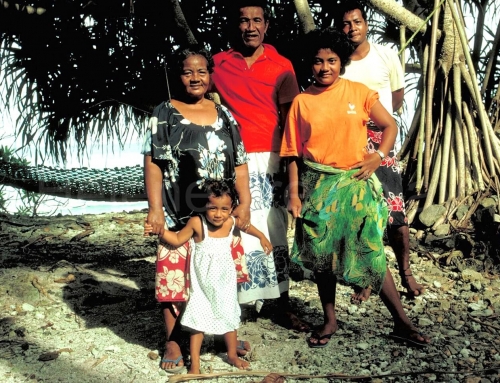

THE REREZ FAMILY

Gustavo Saez Rerez, age 36

Reina Ildaura Rerez, 30

Diana Isela Saez Rerez, 12

Rene, 10

Maciel Milagros, 4

15 chickens

1 dog

1 cat

LLANO LARGO

January 15, 1985

What time is it?

The sound of a truck engine starting up has awakened all the roosters in the village of llano Largo. Their chorus erupts in every garden and echoes across the green shrubby coastal plain. Shifting the gears of his old truck, Gustavo Rerez sets off on the hundred-kilometer trip to the market at Aguadulce, where every Wednesday he sells his tomatoes and watermelons. The profits are the Rerez family’s main source of income, and must cover the rent for the two hectares of land Gustavo farms, the wages for the young laborer he employs, and the cost of gasoline.

5:50. “What time is it?” Every day at this time twelve-year-old Diana’s question comes bouncing over the half wall of cement blocks that separates the children’s bedroom from their parents’. Her mother, Reina, stretches out her arm and pulls the string hanging from the corrugated-iron roof. The harsh light from the bulb drives Diana out of bed. After bathing with a pan of water and brushing her teeth at the tap in the dark courtyard, Diana takes her carefully hung school uniform out of the house’s only cupboard.

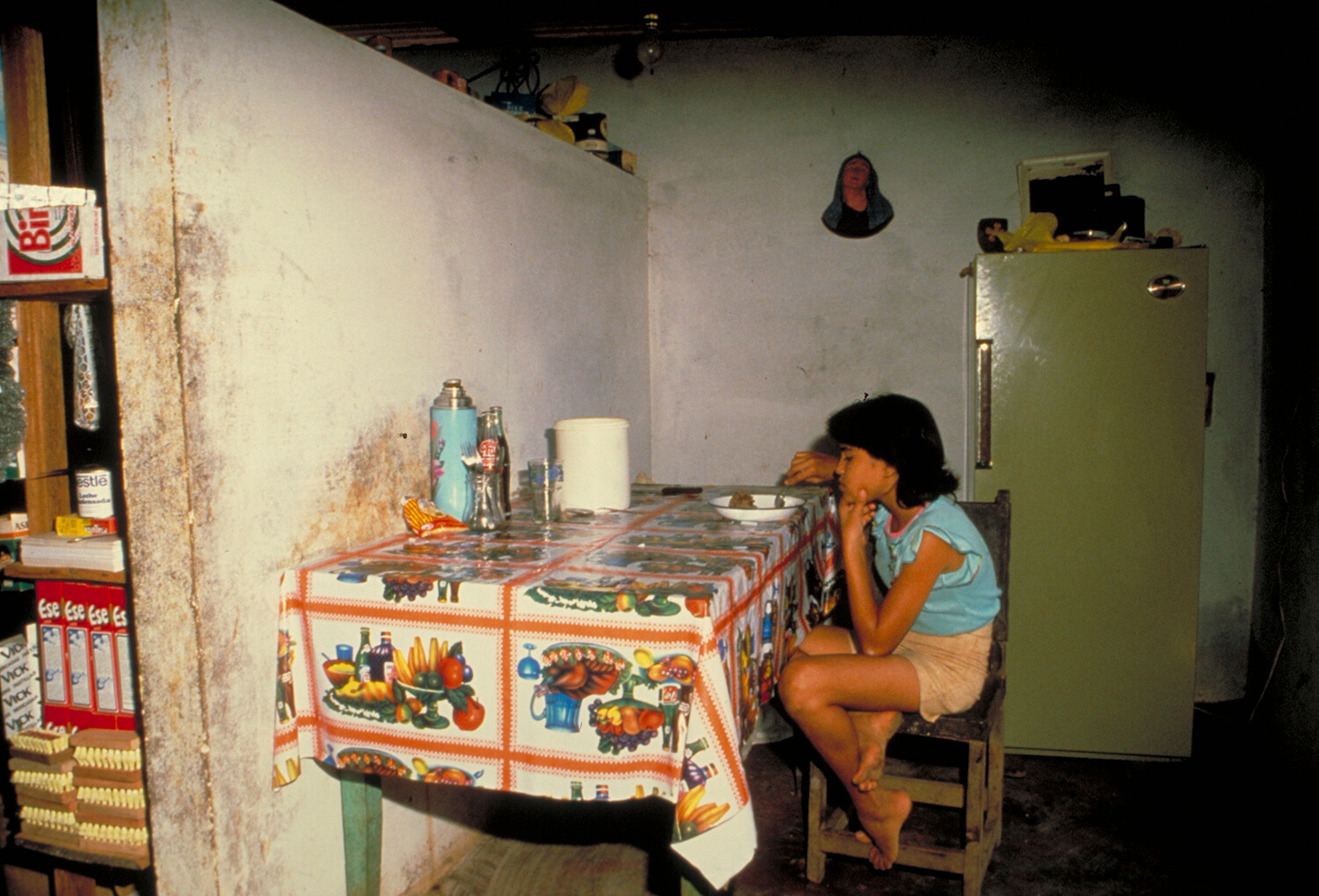

A new source of income for the family

A neighbor has seen the light at the Rerez place and immediately comes over to their stuccoed cement house to buy bread. Still in her nightdress, Reina gets up and serves her first customer. Over the past month her tienda (store) has become a new source of income for the family. The inventory has already doubled, and the living room has been completely taken over by shelves, a counter, and dozens of sacks and boxes. Reina would like to have her living room back, but adding a room now will cost them the same as it did to build the whole house thirteen years ago.

Catching the bus to Los Santos

Diana finishes the oatmeal that her mother has made and, clutching her sandwich in her hand, joins her friend in the street. High school students and town workers alike head in the same direction to catch the bus to Los Santos. The women, balancing on their stiletto heels, walk carefully over the rocky ground. The farm laborers squeeze into trucks provided by the owners of the huge banana and sugar plantations nearby.

The garbage will be burned

7:00. Ten-year-old Rene folds up his camp bed and leans it against the wall of the room he shares with Diana. Without uttering a word, he goes through the same motions as his sister. He won’t really wake up until he gets to the village school and joins his friends. His silence goes unnoticed by his mother, who is rather shy and untalkative herself. Reina sweeps the house inside and outside, collecting a pile of papers and orange peels. The garbage will be burned at one end of the half acre of land she shares with her in-laws.

Anyone bold enough to oppose her?

8:00. Little Maciel appears, yawning. She needs long nights of sleep to recover from her strenuous days. In a few minutes she will disappear and not return until sunset. Her mother never worries about Maciel’s comings and goings. She has two grandfathers, two grandmothers, and dozens of uncles and aunts whom she visits each in tum. Bright and good-natured, Maciel is also tough and independent, and anyone bold enough to oppose her is rewarded with a monumental outburst of temper.

Reina runs after the chicken with a stone

11:00. Reina spends the morning serving her neighbors, who come to buy a pound of rice, a stick of butter, or a can of tomato sauce. From time to time, wholesalers drive up in trucks to sell Reina more stock “This product is imported directly from the United States, senora. It’s excellent!” Reina allows herself to be persuaded. At lunchtime, Reina searches the shelves, trying to vary the usual menu of rice and black beans. Finally she decides on one of the chickens scratching behind the house. The chase begins. Tommy, the dog, refuses to participate, as it’s already much too hot to get excited about a chicken. From his prone position, the dog watches as Reina runs after the chicken with a stone in her hand and deftly knocks the bird unconscious.

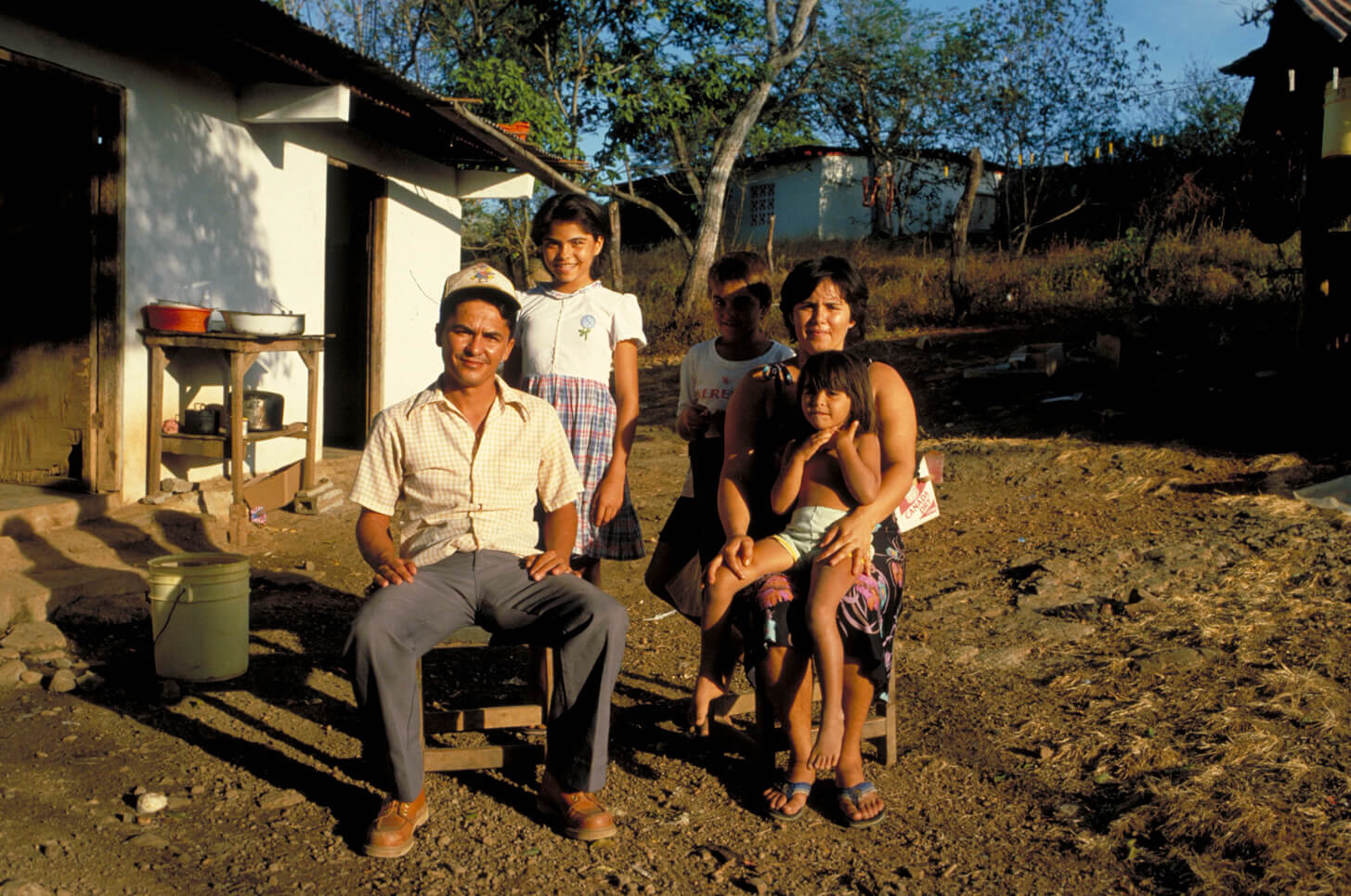

1:00. School is out, and the store fills up with children who have come to spend their pocket money on candy or sherbet. Diana saves her pocket money by walking back from Los Santos, which takes a good hour. She arrives at the same time that Gustavo returns from the market. Behind the house in a thatched-roof shelter that serves as a kitchen, the chicken soup simmers on the open-fire adobe stove. Reina still uses the wood fire instead of her gas stove. It’s more economical, and she thinks the food tastes better. Outside, the family takes advantage of the winter breeze; a scorching one by other people’s standards. In a couple of months, it will be even more intolerable. Old people, like Reina and Gustavo’s parents, prefer to live in their traditional adobe houses with tile roofs, which stay cool inside. like most younger people, however, Gustavo prefers a corrugated iron roof and cement blocks. “It’s hotter,” he admits, “but I’ll never have to repair it.” It’s this decision that forces the family outside two to three hours a day when their house becomes like an oven. No need to hurry. There won’t be any customers; everyone’s staying in the shade.

4:00. Diana installs herself on the front porch, and puts her books and notebooks on top of the sewing-machine cabinet to do her homework. She is a good student, and her hard work earned her a scholarship to cover the first three years of high school. She is very proud of saving her parents the high cost of education, including registration, uniform, books, and fees. Rene is less studious and postpones the learning of the Ten Commandments in his catechism. Today he will go with his father to buy this week’s cow. Every Thursday night, Gustavo and his laborer slaughter and bleed an animal in the yard, and then Reina cuts it up in the kitchen. The meat will be ready for sale by dawn. This is the third source of income for the family. Gustavo and Reina are hard workers, and a well-matched couple. Although not outwardly affectionate and demonstrative, they have organized their life together well. They have used birth control to plan their family so that they will never want for anything. “My children eat their fill, are well dressed, and can go to school,” states Reina proudly. “When I was little, it was rare to see people with shoes; today it’s rare to see them going barefoot. There will be still more progress by the time my children have grown up.”

5:00. The family relaxes on the porch as teenagers stop by to buy a Coca-Cola and chat. All the chairs and most of the steps are occupied and a lively discussion is underway. One of the high school students is worried about going to the university afraid of going to the capital, to such a big city. The girls vie with one another as they discuss the men in their lives, Saturday night’s dance, and Carnival, which is just around the comer. Gustavo is preoccupied with the details of the next junta (community cooperation to build an adobe house) and Sunday’s cockfight. He has a vested interest, as two of his birds will be fighting. Reina passes her family plates of food. Balancing their dinner on their knees, they all praise the chicken with rice.

7:55. “The crickets are singing this evening,” Gustavo observes with satisfaction. “That means that the night will be cool.” Someone notes the time, and the patio suddenly empties. Television sets are switched on in every house. The last hour of the day is devoted to Lionella, a soap opera heroine. The Rerez family take their seats in their living room/store, where the 1V set stands on a shelf. The children balance on sacks of rice and black beans and the parents take to their chairs for an hour of romantic drama that makes Reina cry and makes the rest of the family hungry. They eat oranges, passing the paring knife to each other in silence. The peels pile up for Reina to sweep away tomorrow.

The old people prefer to live in their traditional tile-roofed adobe houses, which stay cool in hot weather. Gustavo prefers corrugated iron and cement blocks: “It’s hotter, but I’ll never have to repair it,” he says Every Thursday night, Gustavo slaughters a cow in the yard. Reina is up all night butchering it on the kitchen table. The meat will be ready for sale at dawn.