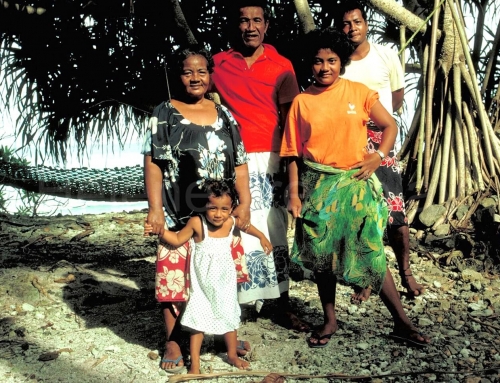

THE POPO FAMILY

Raphael Popo, age 30

Francisca Popo, 30

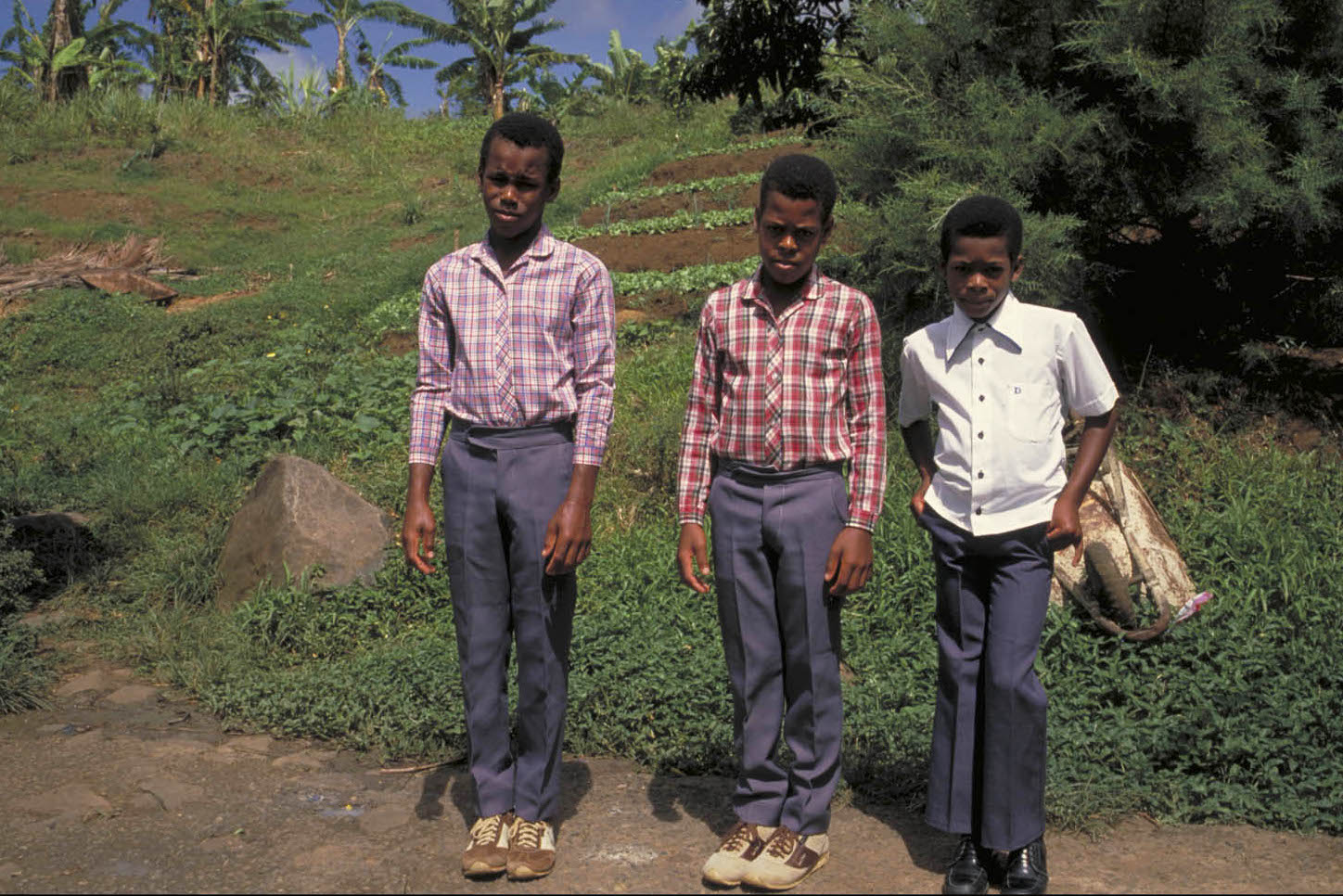

Alvin Popo, 12

Davis, 11

Ron, 8

Delia, 5

4 sheep

3 goats

2 cows

1 dog

5:30. Francisca bangs on the wall that separates her room from her children’s. Her oldest son, Alvin, gets up and walks outside to the kitchen shack to light the fire. The morning mist clings to the lush, verdant slopes of the rain-forest mountains. After Dominica, St. Lucia is the greenest island in the Caribbean.

Half an hour later, Francisca rouses herself from slumber. Every day the child she is carrying feels heavier. Raphael has made coffee. This morning he fills an extra cup; his mother-in-law came yesterday to spend Mother’s Day with her daughter and after breakfast will return by bus to her home in the capital. Seeing that his wife is in no mood to speak to him, Raphael leaves to take the livestock to pasture.

Alvin gathers up yesterday’s dirty dishes and puts them outside on the ground. Then he goes to fill a dishpan with water at the only tap in the courtyard. In her room, Francisca gathers the children’s school uniforms from the cardboard boxes that serve as cupboards. She irons the uniforms every day. Ron takes a basket and climbs to the top of the hill to wait for the truck that delivers bread every morning. Davis, the most studious, is excused from chores, as is Delia, who is still too small.

7:15. A sudden downpour causes everyone to run for shelter. It rains very hard, but only for a short time. In five minutes everyone is back at work. In silence, they listen to radio announcements of the local obituaries. Francisca always listens in case she knows any of the people who have died. The slightest piece of news travels fast on this small island, and commenting on neighbors’ actions is the only excitement in the peaceful life of the country people.

Francisca has pulled out a bucket and sits down beside Alvin. The family’s activities take place here, between the house and the shack that serves as a kitchen. As she does her daily laundry, she gives instructions to Davis, who is making breakfast: “Don’t forget to put a little nutmeg and cinnamon in the hot chocolate. Not too much corned beef on the bread.”

9:00. The children will barely be able to make it to school before the second downpour. They run up the hill, pursued by heavy gray clouds.

Francisca bathes under the outside tap and slowly climbs up the now slippery dirt road to the community health clinic. She is careful. Two years ago she lost a baby when she was eight months pregnant and almost died. This will be the last childa girl, she hopes. Then she will have a tubal ligation. “I have to think of myself and of the children I have already.” Francisca enters the clinic two hours late. With the experience of previous pregnancies, she knew that it was pOintless to come earlier. A dozen pregnant women, seated uncomfortably on hard, narrow benches, still wait their turn.

Raphael has offered to rinse the laundry during her absence and hang it out to dry. A good excuse not to work in his banana grove this morning! He drank too much last night and the mere thought of all the things he has to do exhausts him. But Raphael is not apologetic. ‘Tve got the right to rest a little bit. I’ve never been afraid of work.” He spent three years working the harvest in the southern United States, under an agreement between the United States and the Caribbean governments. “But I’m finished with that slave work,” Raphael says. ”I’ve got what I wanted, and now I want to stay close to my family.”

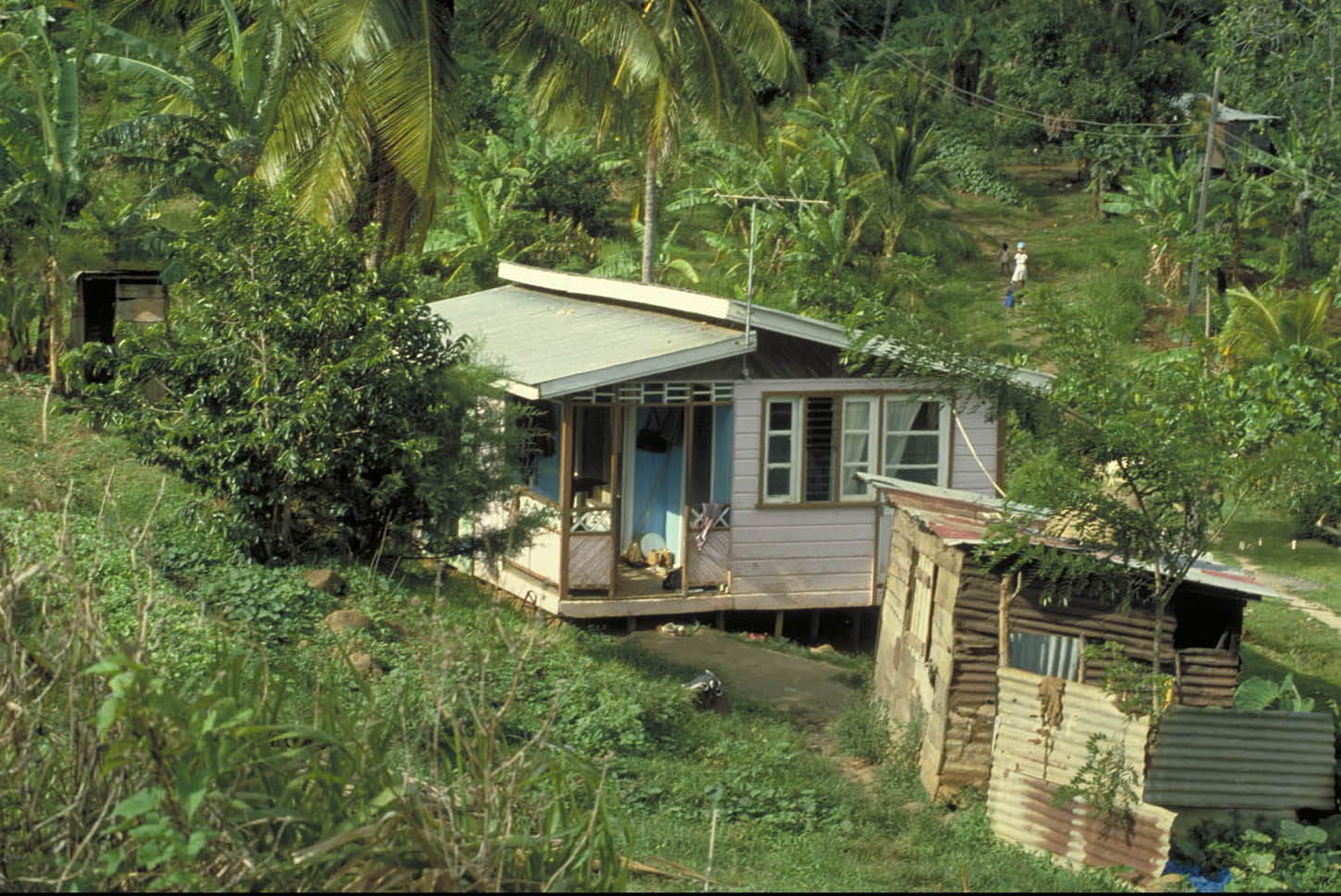

Thirteen years ago, Raphael built his wooden house with his own hands. It has four small rooms and is solidly built. The neighbors sought shelter at the Popos’ when Hurricane Allen destroyed part of the island. “All we need now is one extra room,” says Francisca. They have to wait until they accumulate some savings. “When I think of all the people living around us in mud houses with no running water or electricity, I think how lucky we are.” The new room will be for the boys. They are growing fast and will soon outgrow their tiny room. And it will be built of cement, now that it is no more expensive than wood.

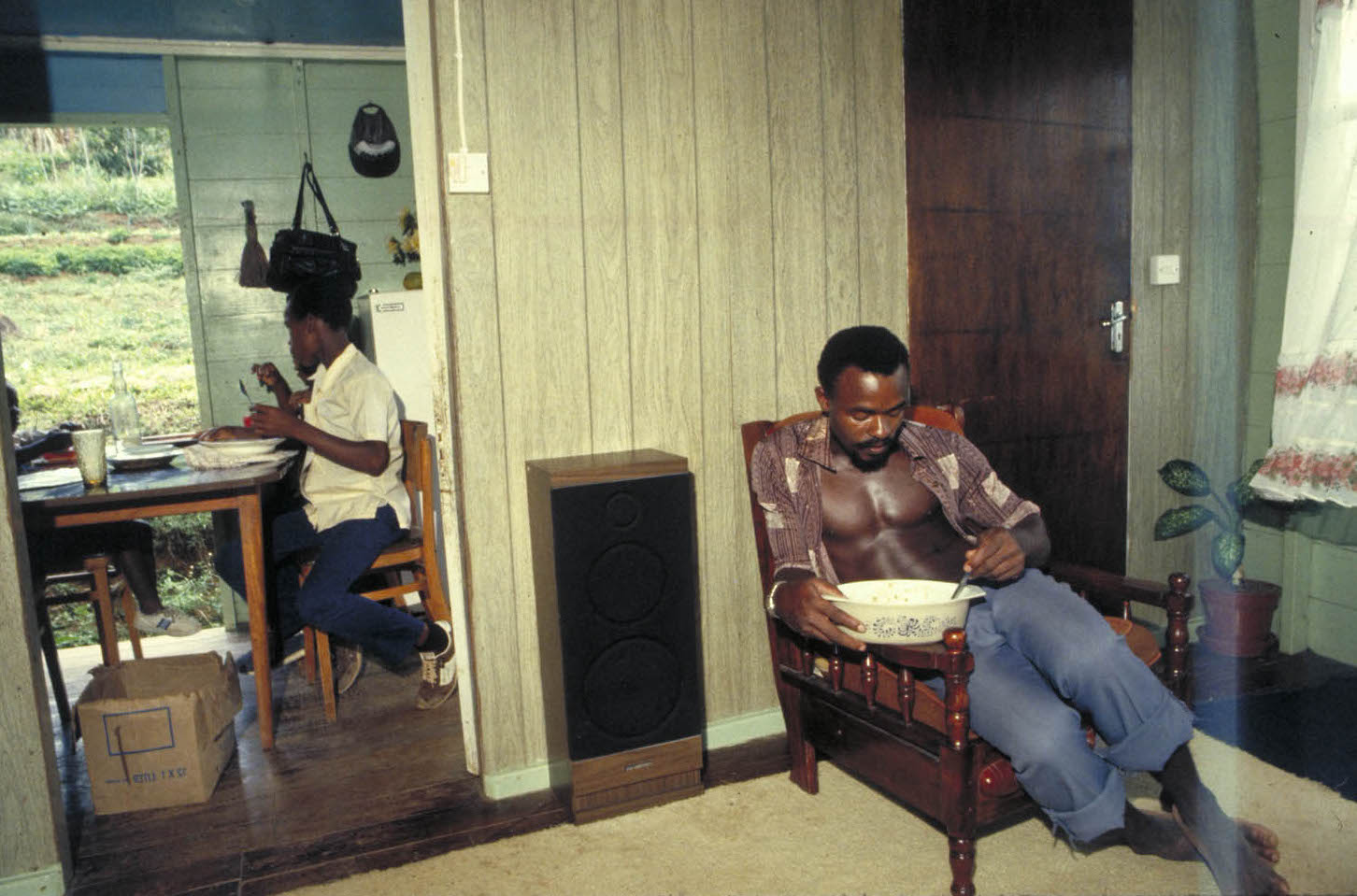

After the first year working abroad, Raphael bought a sofa and the piece of land surrounding the house. After the second, he brought back a television and hi-fi system. Then he installed a tap for running water. Finally he widened the path leading to the house and had electricity installed, sharing the cost with his neighbor.

12:00. Francisca leaves the clinic at the same time as the children get out of school. With Raphael’s help, the meal is ready when they arrive home. Raphael’s willingness to participate in the household chores is a rare quality among the men of this country. It helps Francisca forget all his other faults, the most outstanding being his numerous amorous escapades and the two children he has by other women on the island. Francisca has been angry at him since yesterday, though, when he left her at home and spent Mother’s Day with his buddies. Eventually she will forgive him. They have lived together since they were sixteen. Francisca, however, doesn’t have many illusions about love, even though Raphael decided three years ago to propose marriage to her. “He knows I am a hard worker,” she says, “and he was afraid someone else might notice it and snatch me up.” For his part of the marriage contract, Raphael has promised to be faithful to his wife.

1:00. The children have returned to school, and Francisca and Raphael go out to work. The banana trees must be looked after every day and every stage of their development watched. The Federation that is responSible for the export of bananas has issued very strict regulations, which have to be obeyed, and that takes hours of work. Now they both wrap bunches of green bananas in blue plastic bags to prevent the windblown palms from blemishing the fruit. “They tell us foreigners don’t buy marked bananas,” says Raphael. Tomorrow Raphael will plant sweet potatoes. He follows the instructions of the farmer’s almanac, whose growing seasons are governed by the phases of the moon.

4:00. Francisca is sitting in the shade, giving her swollen legs a rest. Delia has trotted off down the road. She spends a lot of time at the home of Raphael’s mother, their closest neighbor. School is out, but the boys cannot go out to play immediately. Ron carries charcoal into the kitchen, and Alvin goes to feed the cows. Alvin is the hardest worker at home, but Francisca complains about his performance at school. Davis is the most promising student. He lazily waters the garden. PhYSical work doesn’t interest him. His ambition is one day to wear a suit and tie and work in the city.

5:30. Francisca prepares dinner in the cabin. She has given up the idea of having a kitchen in the house. Her husband would never be willing to give up the good taste of food cooked over a wood fire. In the garden, Raphael is planting two rows oflettuce, singing with the radio as he works. They grow a variety of vegetables and herbs, which Francisca sells at the market three times a week, their only regular source of income. The last rays of the sun illuminate the different green hues of the various fruit trees in the valley. Waves of rhythmic music. Boat out of the house. “When there’s music, it doesn’t feel like you’re working,” says Raphael, pouring himself a small glass of rum, which he places on the side of the balcony. He seems a happy man. “To have my own land, my own house, no debts, and no boss, that was my dream. To be free.”