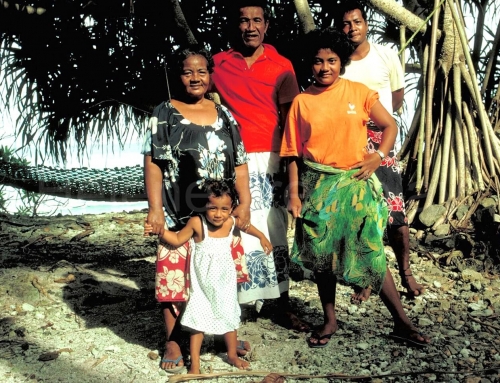

The Steven Bol Adok family

Steven Bol Adok, 48 ans

Nyadang Alok, 36

Nyablac Martha Steven Bol Adok, 21

Cangjwok Steven Bol Adok, 19

Paul (Pawli) Steven, 17

Acol, 15 (fille)

Obaj, 13

Nyajina, 11 (fille)

Nyababy, 6 (fille)

Aur, 2 yrs1/2

Deux chats

Malakal,

2 Mai

Il y aura de la bière à vendre aujourd’hui

4 h.30 L’émanation de la bière artisanale qui a mijoté sur le feu toute la nuit s’élève à travers l’enceinte avant le soleil. Nyadang Alok se lève instantanément du sol où elle dort avec sa famille. Elle se dirige vers la cuisine.

L’odeur qui flotte dans l’air si tôt est l’appel à ses habitués qu’il y aura de la bière à vendre aujourd’hui. La cour, est bien connue. Hier, c’était la femme du «tuku» (hutte) voisin qui vendait. Ils se relaient parce que c’est leur seul moyen d’obtenir de l’argent des hommes qui, disent-elles, ne leur donnent pas assez pour leurs enfants.

Le ton de leur mère est convaincant

5 h.10 Nyadang Alok secoue ses enfants un par un et leur ordonne de se lever et de nettoyer la cour. Le ton indiscutable de leur mère et la force de ses bras sont convaincants et ils se lèvent sans envie de leurs matelas faits de sacs d’aide alimentaire en plastique usagés. Nyadang Alok traverse la cour avec une bouteille d’eau se lavant les dents, crachant la nuit et disant à Nyajina d’aller chercher des charbons ardents chez les voisins parce que le feu s’est éteint.

Le thé sera prêt dans une heure. Plusieur des huit enfants de Nyadang Alok sont absents. Martha reste avec un oncle dans la zone est de Malakal pour pouvoir se rapprocher de l’école jusqu’à la fin des examens. Cangjwok est quelque part, dans l’armée nationale du Soudan. Pour le salaire, peut-être est-il à combattre les rebelles du Sud. Pawli est chez une tante du village depuis le début des vacances scolaires. Acol est parti hier avec Obaj pour cueillir le «tugo», le fruit du palmier dolib, dans un village voisin. Ils les ramèneront aujourd’hui pour vendre au marché.

Il y a des serpents et des ennemis

Au lieu d’attendre le thé et avant d’aller soulever les filets qu’il a laissés la nuit dans le Nil Blanc à proximité, son mari Bol Adok préfère aller à son stand habituel pour prendre un verre de bière avec d’autres hommes. Les boissons locales sont nutritives et remplissent son estomac. Il enivre aussi toute la ville en fin d’après-midi.

En direction du poste de contrôle militaire, des milliers de têtes de bétail quittent la ville pour paître dans les zones rurales environnantes. Le bétail et l’éleveur, connaissent la sortie. Tous deux ont essayé d’autres routes, mais beaucoup sont morts ou ont été estropiés et mutilés par les mines terrestres. Malakal est protégée la nuit contre les attaques des rebelles par les mines terrestres. Chaque matin, certaines sont levées aux points de contrôle, permettant aux résidents de sortir dans leurs jardins pendant la journée. Ceux qui partent dans les villages portent des bâtons et des lances. Il y a des serpents là-bas, ainsi que des ennemis. Le pays est en guerre civile et ces personnes ne font pas partie des mouvements rebelles. Malakal est la capitale contrôlée par le gouvernement de la province du Haut-Nil au Sud-Soudan qui veut l’indépendance du gouvernement de Khartoum dans le Nord et sur laquelle les rebelles et l’armée nationale se battent depuis 30 ans.

They rent a sleeping “tuku” (hut)

Nyajina is left to help her mother and is now sweeping the courtyard. The straw-fenced compound is on the corner of a main white, sandy vehicle road and a smaller one only passable by four-wheeled drive vehicles. So the courtyard is often a shortcut for family and certain friends of the neighborhood. One woman crosses saying she is going to a dance as the council of ministers the city’s governing body is entertaining guests. Everyone heard about the boat that arrived yesterday from Khartoum in North Sudan with important people on board. The Malakal “köwot” (gossip) circuit is the quickest, most efficient way to pass on information.

The yard does not belong to the Steven Bol Adok family, they just rent one sleeping tuku and share the compound with a women who rents a cooking-hut. They share with Elisabeth Deng whose front door is so close that it is natural to share the same fire. Elisabeth is a widow. Her husband was a teacher. In 1994, along with four other teachers he was arrested. They were eventually released but diedone-by-one afterward. “They did not survive their torture,” says Elisabeth, raising her daughter as sister for Nyajina and sharing her firewith Nyadang Alok. She is part of the family.

Part of the Shilluck tribe

It is part of Shilluck tradition to have at least three huts but only few have managed this in town where land has to be acquired. Furthermore, Bol Adok is not sure where exactly it is secure to buy and build.

In 1986, the Nuer, one of the two main tribes fighting for Southern Sudan’s independence, attacked many Shilluk villages who have never been part of the SPLA (Sudan Peoples Liberation Army). The Northern army retaliated and there followed numerous massacres of civilians.

The Shilluks are black Sudanese who have always lived in villages along the west bank of the White Nile. The guerillas want independence from the strict Islamic rule of Khartoum which wishes to place Sharia law on all Sudanese, even those in the black South who are Christians or animists, following traditional African religions. War has been raging between the two sides off and on for 30 years.

That dreaded year of 1986, Bol Adok’s entire village of Aleel fled towards Malakal where people from all over the Upper Nile province were taking refuge, leaving their dead behind. After securing his wife and children with in-laws, Bol Adok went back immediately to bring the family cattle further up the Nile and stay with them. One day, he had to leave the cattle to come and secure the harvest in fields near Malakal but he was away too long and when he returned, 125 had been stolen.

Cattle is central to life and culture

He was so upset that when he came back he promised himself he would not have cattle anymore. As a Shilluk, cattle have always been the central part of his life and his culture, but he says he does not want the trouble no more. He then build a tuku at the edge of the Southern zone where the Northern authorities had made land available for the displaced from Aleel and other villages. Then in 1992, there was an attack on the Malakal’s government garrison. The SPLA rebels entered the town from the Southand, once again, Bol Adok and his family had to take refuge inside the town. Now, they dare go any further, feeling safer renting this one tuku.

Even if Bol Adok hopes that war will one day be over and they will go back to the village, time passes. Four of his eight children were born here in Malakal where schools and a hospital can be found. He knows his family life will now always be somehow linked between village and town.

The town is villages set side by side

6.30 One of Nyadang Alok’s friends comes to have tea before going tothe hospital. Her son has gotten into a fight with the son of Odok Dung the Leader of the Southern community, and one of his eyes is open and swollen. The chief is away and the father of her son, she complains, is not giving it any attention so she is bringing him to the hospital where, at least, she will get advice, a little more information about health and, more important, calm her worries.

Elisabeth Deng leaves with her. She works as messenger at one of the government offices. Her daughter will be safe in the yard with the other children. Built like villages, set side-by-side, Malakal is widely spread out. The two women will have to walk almost 90 minutes before reaching the central part of the town.

Malakal streets are busy as everyone is trying to do as much as possible before the mid-day heat strikes.

He is planning to hunt for a hippotamus

Bol Adok fishes on the Nile every day and runs his life alone. But what he likes most is to be at the village where some of his family members have ventured back, half-believing in one of the many peace-treaties between north and south, or simply ready to die in their homes. Tomorrow Bol Adok will go that way. He is planning to hunt for a hippotamus. This is his greatest pleasure and he speaks about it with pride and energy.

All hippos must be brought to the king who is elected by the people and does not come from a royal clan. Bol Adok said he has brought two in his life but that was to the former king. He plans to bring him one soon. The Shilluk king has a lot of influence over his people’s live and is believed to have divine powers. However, in Shilluk tradition the king can be deposed or killed if he becomes seriosuly ill or senile. “This is king number 26 , he is an educated man and,” Bol Adok adds, “he has 30 wives.”

The hippo hunter is very disappointed to have only one wife and until he can buy one more, he thinks he will not have suceeded in life. “A man is respected and rich when he has many wives” and this is what he wants he says, determined to get his greatest wish.

There are many reasons for 30-years of war, but cattle-stealing is onereason tribes of this part of the South do not fully trust and sidewith the rebels who fight for an independent federated south. So evenif the king has set the price of wives at 10 cows — 100 for a Dinka, the other main southern tribe in the liberation war, to buy a Shilluk wife– which is much less then before, cows are now rare and expensive.

Today it is a luxury to even buy one wife. And now his sons are big and cows will soon be needed to marry them so the prospects of Bol Adok ever getting a second wife are being diminished every day. And this he sees as a failure.

8.30 Bol Adok finishes his beer and heads to the market, dreaming that his king will give him 10 cows for the hippo he will deliver. The centralzone’s big market is already lively. Everyone sells something, from a handful of grain to many cows, but no sheep. Last month all sheep died of disease, as well as 200 people in town from an outbreak of cholera, causing them to die from dehyfdration brought on by vomiting and diarrhoea. The epidemic is just beginning to be under control after an urgent vaccination operation by the UN. All Bol Adok’s children are safe but he was not really worried. “Children are just people,” he says accompanying is words of gesture meaning that they are not important. Bol Adol is sure he will make children until the end of his life.

8.30 This morning Nyadang Alok has her mind set on Martha’s agenda. She is now entering school to pass the Sudan school certificat. She has finished her secondary school if she passes this exam she could continue to further her education. Martha says she would like to study economics at the university in Khartoum.

Pawli will be the next one if he passes to eighth form but has not yetcome to get his school results. His mother says he likes school unlike Acol who has only completed three years of school and not caring if she passes or not. Thirteen-year-old Obaj has not started school yet. Obol Adok says it is better to start school later when children are more ready to learn.

10 a.m. Behind the walls of the compound, the beer drinkers have been coming all morning –Dinka, Nuer and Shilluk — one or two at a time , sitting down to half a litre of beer and walking off to their daily survivaloccupations. Drinking here together, they try to put their differences aside while on the outside, talks go on and on between the government of the North, guerillas of the South and international peacemakers, to find away to finish this never-ending war and hate.

Sheltered in the shade, the beer drinkers are not seen from thestreets and the courtyards now seem empty. In fact, most are left to children caring for other children and the Asian martial arts, popular with the boys playing “fighting”. But when he was a boy, Bol Adok did not play war, he lived it. At 16, he was then attending a Christian boarding school when the guerrilas who wanted an independent Southern country entered the school forcibly took away the most healthy and strong boys. For the next five years Bol Adok lived in the bush carrying the material the rebels needed continue the war. Since then, from fighting to peace-treaties, to other rebels and other reasons for war, Bol Adok has never found rest in the most misunderstood and forgotten war in the world.

11a.m. Nyadang Alok walks to the small southern zone market to get sugar that she buys 250 gr-at-a-time. She will now cook the first meal of the day. She never goes out of the yard without tying her “lao-cloth” over her left shoulder. Shilluk men tie an identical cloth on the right. She is tall and her step is wide, firm and steady and she is back quickly. Malakal is in Shilluk territory, bordered by Nuer and Dinka territory. Many of South Sudan’s tribes can be identified by the facial tattoos and differences in clothing. The tattooing isritual cutting with a razor blade or knife which is then coloured in some tribes or clans to make it stand out. The scars are regular and run in various angles. It is usually done when quite young.

Once the Dinka declared that they would kill everyone who was not Dinka. Dinkas, who had not done so, had their entire face tattooed as was their custom, but many young people of other tribes stopped tattooing their face and bodies, hiding this way their tribal identity. None of Nyadang Alok’s children and none of the other young people in the yards around have the Shilluk marking on the forehead. “We do not want to go through the suffering,” they say, not caring anymore about this ritual identity.

1 p.m. It is now very hot and the children have sheltered in the shade ofone of the huts. Some are making sculptures with mud. The patterns are the ones they know: soldiers, guns, and army vehicles. Others play “mother and father”, the girl making believe they are selling beer and the boys pretending they are drinking it.

2 p.m. Bol Adok has taken refuge in the hut from the heat. Voices announce a visitor. Leaving behind his old crazy mother who talks to herself under her blanket and spends the day without much attention and is never seen, he walks out to welcome his nephew passing by for a visit. The young man’s father, Bol Adok’s last brother, was killed three years ago by the army. At that time Bol Adok was angry and thought of joining the rebels to satisfy his feelings of revenge but decided he was too old. This nephew, now the only man left of the family, is as important to him as if he was his own son. If only Cangjwok, his elder son, could be like him.

Cangjwok joined the national (Northern) army. He is well paid — five times more then a teacher. Bol Adok says this is the reason so many southern boys join the North’s army. Those who join the SPLA do so because they believe strongly in fighting for the independence of the south. But what makes him the most disppointed with his son is that he never sends any money home.

3 p.m. Acol and Obaj are at the market lined up beside other chidren who have goods to sell. The palm fruits are on the ground and they they wait for buyers to come by. This way they make their pocket money. Obaj is proud that he bought his modern T-shirt and caps with his own money. Obaj is business-like, he wants more things.

4 p.m. Everyone is waiting for Martha. She has finished her exams and has not returned home. She is scared and is hiding at her uncle’s. She would like to disappear completely from Malakal because just before her important exam, she learned that her father, has sold her, for cash, to an Arab Muslim man to be one of his wives. Even if the young girls appreciate the fact that Muslim men do not drink, their marriage customs are different. It is also well known that they never take the black women of the south as wives but as slaves and servants. Martha does not even want to attend today the six year wedding anniversary of a Muslim girlfriend. Martha is afraid that she will be taken away.

Home in South Sudan