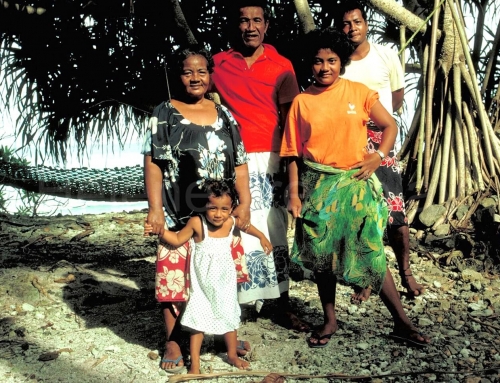

THE VELÀSQUEZ PÉREZ FAMILY

Benjamin Velasquez Pérez, age 36

]ohana Maria Velasquez, 31

Dalila Guadalupe Velasquez, 10

Nemias Nicolas, 8

Jonathan Crispin, 5

Maria Guadalupe Pérez, 64

7 chickens

5 ducks

The iridescent mosaic of terraced fields

6:00 Benjamin turns on the radio a little too loud but nobody reacts. He shuffles towards the door, climbing into the trousers that he left on the back of the chair the night before. This year it is Benjamin’s turn to pick up the mail from Totonicapan as part of his volunteer work for the community. His plastic cowboy hat on his head, his stomach empty, he marches off quickly.

When he opens the door, the cold, thin mountain air takes his breath away. It will take him twenty minutes to climb clown to the valley where the bus passes by. The path on the edge of the cliff is so narrow and steep that it takes all his concentration to navigate it.

Above Benjamin is a majestic green and yellow sweep of mountains embroidered with an iridescent mosaic of terraced fields. And as always, the silhouette of the Santa Maria volcano looms in the distance

“The children are wasting their time in school”

Inside their cool adobe house the children are happy to remain snuggled under their warm blankets while their mother, Johana, lights the wood fire. They are on summer vacation. Johana thinks that her children are wasting their time in school. The classes are overcrowded, often sixty to seventy children in each room, and Johana does not like the teachers. “They come from the city to teach but don’t bother to learn Cakchiquel [the native language],” she complains. “Our children have to learn Spanish to be educated.”

She is an artist

7:00 Johana drinks a cup of coffee and goes out on the patio in the back of her house to begin her day’s work.

Like most of the residents in the Juchanep township, she is an artist. Using brightly colored cotton twine, Johana weaves beautiful belts of intricate patterns. She bangs one end of her weaving on a post and attaches the other end to a leather harness around her waist. lt takes her four days to finish one belt, which she sells for 4 quetzals ($4.00) to a wholesaler. lt probably cost her three-quarters of this amount to make each belt, but Johana and the other artisans do not conduct their business in a modem fashion, which computes profits in terms of time spent and materials purchased.

It could be dangerous for Rachel to try to find out.

The children are up and scampering about their mother. When they were small, Johana carried them on her back as she wove. By the time they could walk, their mother’s work had already become a part of their lives and so the children accept her lack of attention towards them. They are independent, and the older ones naturally look after the younger. Now they leave for their grandparents’ house across the patio. It’s a lively home and their gentle grandmother is always willing to spend time with them. Their aunt Rachel and uncle Nefteli also live there. Rachel is a widow who has returned home to run the household after her husband was shot to death. When asked who killed him, she replies, “Who knows.” In view of the country’s current social instability, it could be dangerous for Rachel to try to find out.

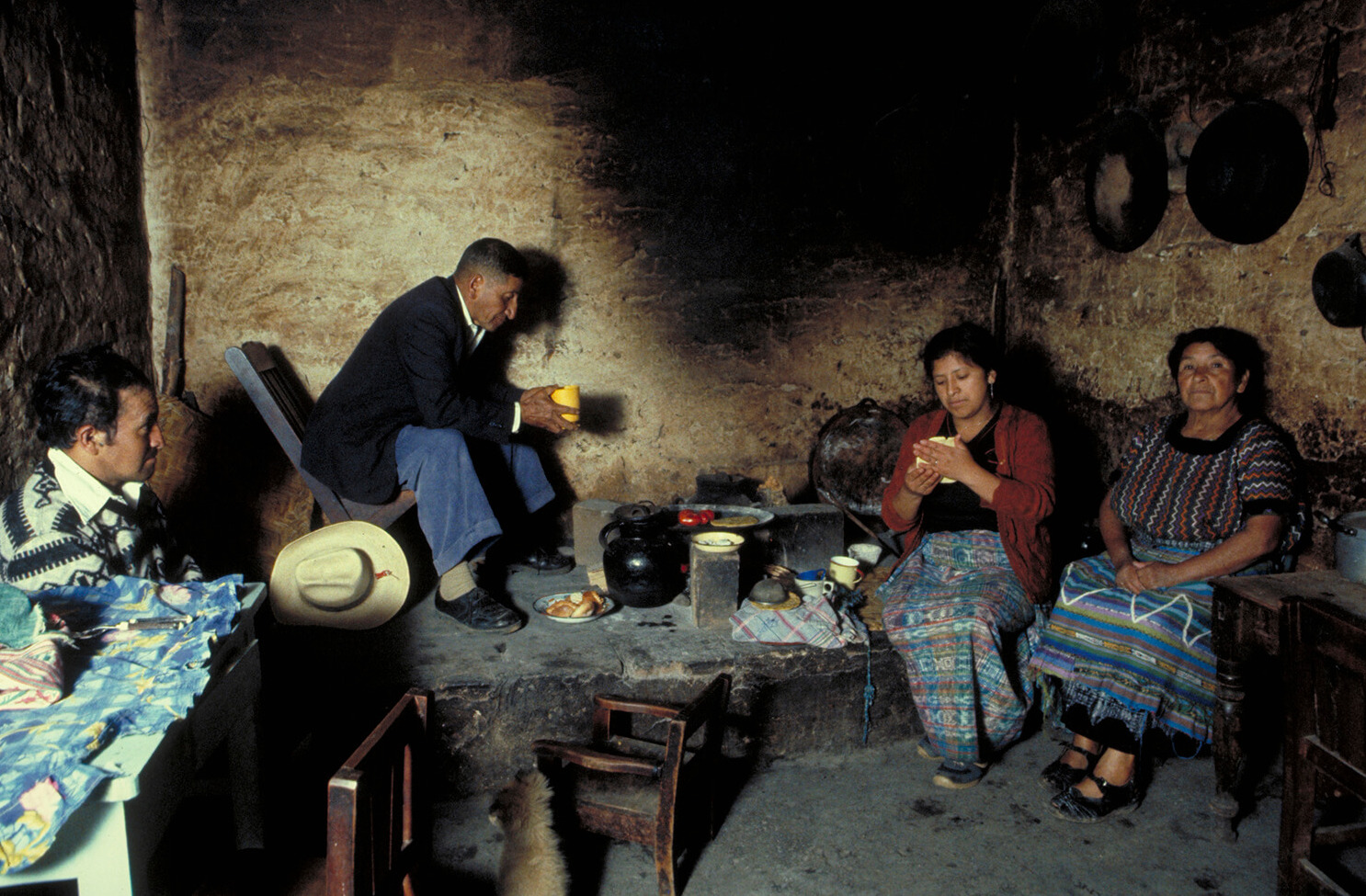

“Buenos dias, Mama. Buenos dias, Papa. Buenos dias, Tia…”

Now she makes tortillas for breakfast. Afterward she will change her old running shoes for a pair of dress shoes and go into Totonicapan to do the shopping. Their arms crossed in front of them, the children bow slightly and greet each of the adults present, as is their tradition. “Buenos dias, Mama. Buenos dias, Papa. Buenos dias, Tia Rachel. Buenos dias, Tio Nefteli.” The adults return the greeting and Grandfather blesses them.

This tradition has been lost in many Guatemalan homes, but Grandmother makes sure it is observed by her family. Breakfast begins like every other meal, with Grandfather sitting near the fire saying grace. Grandfather was baptized and married as a Catholic. But his faith weakened over the years, and one day some particularly persuasive Jehovah’s Witnesses got his ear. Grandfather made up his mind then, and the family left one church for the other. Now Grandfather spends several hours every day reading the Bible and spreading God’s word.

8:00 After eating tortillas, eggs, and chili sauce and drinking a good cup of coffee, Tifo Nefteli bows, thanks his parents and sister, and leaves for work. He is a weaver and will spend the next eight hours at a large loom in a small, dimly lit adobe shack.

Weaving was invented by Ixehel, goddess of the moon

Mayan myth has it that weaving was invented by Ixehel, goddess of the moon. In ancient days weaving was the sacred duty of women and farming the sacred duty of men. But land has become less plentiful in modem times and men have taken over many of the big looms.

lt takes Nefteli three and a half days to weave a corte, a piece of cloth seven yards long which will become a colorful skirt when wrapped around a woman’s waist. The skirts are tied with long belts like those Johana makes. A traditional Quiche woman will have two skirts, one for everyday wear and one for special occasions. The woven colors are dazzling, and the designs reflect each region and ethnic group. They are old Mayan patterns influenced by the art of the Spanish conquistadors. Nefteli dreams of having a wife who still dresses in a corte, but the younger Indian women are becoming more and more Westernized.

Like his sister Rebecca, who is a nurse in the city, they refuse to wear the traditional clothing, preferring shirts and trousers.

Three acres of land, the fruit of his lifetime’s labor

8:30 The children go out to the corn fields to play on the dirt paths between the rows. The corn will be ripe in twenty days. Tired of the long vacation, the children look forward to the harvest. At last they will be able to share in the family’s work. The corn for the year’s tortillas will have to be picked, dried, and stored. Later the oats and wheat will be cut. This family is fortunate. Grandfather owns twenty-six cuerdas (almost three acres) of land, the fruit of his lifetime’s labor.

10:30 Benjamin returns from Totonicapan and climbs up to the top of the mountain to cut wood for cooking. Sometimes he brings back enough for Grandfather to sell for lumber. In three weeks he will no longer have time to do this, for he will go to work for the large landowners. Benjamin hopes one day to buy a field of his own-a daunting prospect in a country where farmland sells for around $4,000 an acre.

Creating things of beauty

1:00 Johana joins her children in Grandmother’s kitchen. They eat tortillas, little tamales, and broth for lunch. There is time for only a moment’s rest, a brief conversation; then it’s back to work. Grandfather loses himself in his Bible, and Nemias and Jonathan look for new games to play. Johana takes only one day a week to go to the city to shop and bathe in the warm water of the large public baths.

Nevertheless, Johana is peaceful and content-perhaps because much of her work involves creating things of beauty and her family keeps alive traditional values and rituals.

5:00 Dalila is happy to finally have work of her own and goes off proudly to the mill to get their corn ground, carrying a plastic bowl on her head. Her return tells Johana that her workday is over. As she puts her weaving aside, Benjamin appears with a load of wood on his back. He dumps the wood in a corner of the patio and enters the house to light the cooking fire for his wife.

Time to receive grandfather’s blessing

7:00 It’s time for the children to give their grandmother and Tia Rachel some peace and quiet, to receive their grandfather’s blessing, and to welcome home the artisan who has once again resumed her role as homemaker. The warmth of the fire replaces the warmth of the day’s sunshine, and Johana’s hands busy themselves with corn dough so her family can eat tortillas. The weary woodcutter showers with a pail of cold water, and all the people in the countryside light their kerosene lamps and send their children to bed.