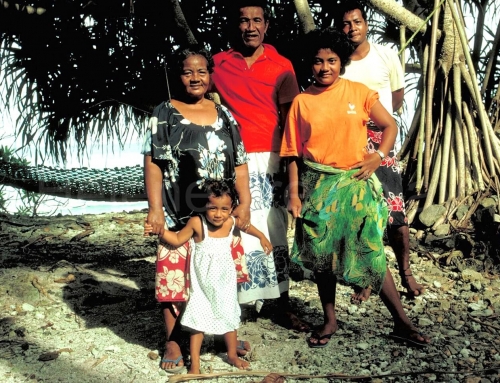

Aram Terewati’s family

Terewati, aged 34

Bakae Teteki, 35

Ritang Aram 10

Teteki, 7

Tabauea, 4

Teikakee, 11 months

Mimrota, 63

4 pigs

2 roosters

2 dogs

1 cat

Utiroa village

January 9th, 1988

Will the household function without her?

5:00 Teikakee’s short sharp cry is immediately silenced by the breast, which his mother, Teteki, lying beside him, puts into his mouth.

6:00 Ritang has slept at her grandmother’s house. At 10 years old, she already runs the household; at least, it seems not to function without her. “Ritang, do this, Ritang, do that,” is heard all through the day. Now she takes a water pail from the bamboo counter in the middle of the yard to fetch water at the nearby well. When she returns, she washes the teibu, the empty coconut shells her father will use to collect the toddy (coconut palm sap).

As long as the oldest can remember

Teteki ducks out of the mosquito net, reaching for the small basket of tobacco that always sits on the floor of the open-air one-room house. She rolls a cigarette for her husband, Terewati, who is already up and can be heard, like the men in every Utiroa household, sharpening his knife on a rock. He tests it on his hair every so often to make sure it is really sharp; then picks up the coconut shells and leaves, whistling.

For as long as the oldest person can remember on the island of Tabiteuea, from one end of the small Pacific atoll to the other, the day begins with men singing. They sing in the morning and evening when they are in the coconut trees fetching toddy. The custom is said to have begun to warn any woman using the bush for private matters that there was a man up in the trees who might see her.

It’s not a simple thing

Getting toddy is not a simple thing. The nourishing sap is collected from a coconut palm bud whose young shoot must be bent slowly during several days so that the sap can run down into an empty teibu. The bud is cut very carefully, so that the sap will flow for a day but the bud will not be ruined. The quantity of toddy depends, not on the size of the bud or the tree, but on the quality of the man’s cut. This delicate operation Terewati now performs at the top of tall coconut trees.

The beach is their toilet

7:00 One is always near the sea on the atoll of Tab North, as the 20-kilometre long island is no more than one kilometre wide at any point. Teteki walks with her two youngest to the lagoon side of the island, whose coral reefs keep the rough seas calm and whose change of tides over its white sandy bottom turns the sea every shade of blue possible. Teteki joins the other villagers squatting near the water, their backs to the reef. The beach in all its beauty is their toilet.

Back from the shore, Teteki squats under the low thatched roof that serves as her kitchen. She starts one wood fire on one side for breakfast; on the other side, she lights a second to dry the copra, the coconut meat. Copra is the Aram family’s only source of income. No other cash crops grow on the poor soil of this coral atoll.

The ability to navigate by the stars and birds and clouds

Ritang’s broom accompanies her father’s song. She sweeps the dead breadfruit leaves and dry, empty coconut shells into a pile on one side of the yard. Grandmother Mimrota watches Teikakee. The unprotected well and the sharp coral rock that forms the ground make it impossible to let him go unattended. He is quiet in Grandmother’ s care and, if necessary, Teikakee will use her own dry breast as a pacifier.

Bakea believes that she is responsible for making her mother’s last days on earth happy and peaceful. Both she and her husband are grateful for the skills their parents taught them: the ability to forecast the weather, navigate by the stars and birds and clouds, build canoes and cut toddy. It is unlikely the couple will now have the time to pass these skills on, as their children will be in school, learning other things.

The Aram family is their first conquest

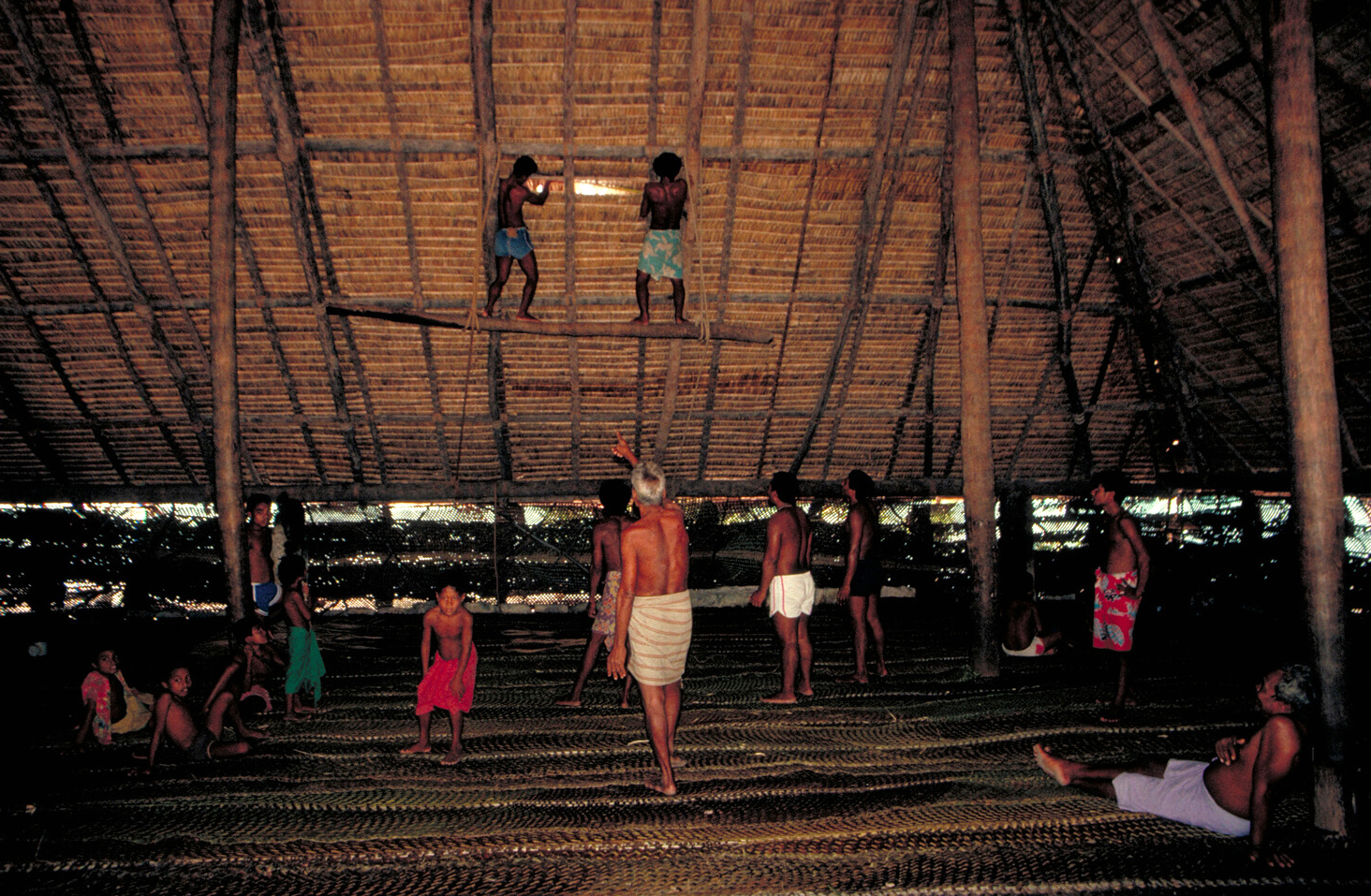

“Ritang, take the baby,” says Grandmother. She goes to sit in front of her old rotting house and starts weaving pandanus leaves. Her own house badly needs repairs, but the leaves she weaves this morning are for the maneaba, the village’s large meeting house, where all decisions are made, in the presence of the elders.

Today, except for high school students, who study on another island, most of the village will meet there. Aram Terewati, however, cannot be with his people. He has a meeting in another village in the small maneaba the Mormons have built to attract converts to their faith. The two missionaries have been on the island only a short time, and the Aram family is their first conquest.

Hoping to begin a new era of peace and friendship

11:00 Bakea goes to the maneaba with her neighbour, both women pulling their piece of leaf work for the roof repairs. A week from now, the whole population of Tabiteuea South, the neighbouring island, will visit in their canoes, and Tab North is getting ready for the great event. The two islands have a history of violent conflict and the people are considered the most aggressive and dangerous in the country. Differences are still resolved with bush knives. But on this historic day the islands will compete in sports, forget their differences and, everyone hopes, begin a new era of peace and friendship.

At 10, she pouts about having so many duties

1:00 Bakea has been too busy to get fresh seafood for lunch, so they’ll have smoked fish. While her mother prepares the food, Ritang, who just finished washing the family clothes, walks around with Teikakee on her hip, trying to keep him content. In a few years, she’ll take on new responsibilities as a woman. After her first menstrual period, the old women of the village will teach her their skills: cooking, and the intricate weaving patterns used in mats, baskets and hats. Sometimes Ritang pouts a bit about having so many duties. She is relieved that this baby is the last sibling she will be taking care of. Her mother is having contraceptive injections: she does not want any more children.

Work today for their 10-year-old daughter’s future marriage

2:30 Naptime is over. Grandmother starts cracking coconuts and laying the meat in the sun. Terewati and his wife Teteki leave for one of their garden plots. They bring the dry leaves that Ritang swept up ta use as fertiliser in one of their six babai pits. These large taro-like plants need five to 10 years to grow to harvest size. The plants the couple will work on today are intended for their 10-year-old daughter’s future marriage.

Working off the island.

The starchy root of the babai was once the main subsistence food of the islanders, but today they prefer buying rice and canned foods. For this they need cash, and more and more islanders seek jobs to earn money. They work on ships or move to the capital island. With their income, they change their lives. They built with cement, buy stereos and play foreign music and exchange their bicycles for motorbikes. Terewati thinks this is all fine, but not attractive enough to merit working off the island.

Traditionally, the kin group owns the land

4:00 The children have joined their parents – Teikakee, as usual, on his older sister’s hip. On their way back, they pass through the garden, gathering the fallen coconuts, which Terewati puts into a bag and carries home. Terewati does not know how much land he has in the five dispersed family gardens. Traditionally, the kin group owns the land. Registration of the land according to individual ownership began under colonial rule, but Terewati, like most I-Kiribati, does not consider it very important. No one ever comes home from the garden empty-handed. The children pick up dry branches for firewood. Hearing impatient crying, Teteki runs the last steps home with her load and pulls up her T-shirt to calm her hungry baby.

A bag full of coconut as payment for tobacco

5:00 Terewati takes Teikakee in his arms while he sends Ritang to the store with a bag full of coconut as payment for tobacco and tinned fish for the evening meal. Around him, the children pick the coconut meat off the drying mats and put it in bags. In the west, a red sun is setting, while the eastern skies are dark and heavy with the evening rain. Once the ground is clean, each family member will take his turn with the pail to shower.

The silence is broken by the wind rising

8:00 The family sits in the dark in front of the house. Suddenly the silence of the night is broken by the wind rising. In less than a minute it is pandemonium. Teteki and her husband run to untie the roof straw hanging on each side of the house. Then they fasten the floor mats to serve as shelter. “Ritang, Ritang,” Grandmother runs to her house, calling her grand-daughter to follow. The rain starts.

Terewati sits with Teteki outside the mosquito net while she finishes her meal. Before climbing into bed beside their children, Teteki turns down the oil lamp. The day surrenders to sleepers’ sighs and the sounds of wind and water.